"The Date and Authorship of The Two Gentlemen of Verona" by Gabriel Egan with Brett D. Hirsch1

Abstract

The Two Gentleman of Verona is commonly identified as one of the first plays, perhaps the very first, of Shakespeare's career, and dated between 1585 and 1595 depending on just when one supposes that career began. This paper will survey the arguments for The Two Gentleman of Verona's place among Shakespeare's first plays. Internal contradictions and inelegant passages have variously been attributed to dramatic immaturity and stratification arising from layers of authorial and/or non-authorial revision. Computational stylistics in the form of John Burrows's Zeta test will be used to look for evidence for stratification as an alternative to the currently dominant theory that the play's irregularities and unevenness are due to the dramatist's immaturity. The play was first printed in the 1623 Folio and the only firm external evidence for dating is Francis Meres's mention of it in Palladis Tamia in 1598. The delay between composition and publication gives plenty of scope for the Folio text to reflect subsequent reworking, for example to conform to theatrical censorship or changing conditions of performance.

Research Context for the Play's Date and Authorship

The first published attempt to establish the order in which Shakespeare's plays were written was Edmond Malone's, based largely on Edward Capell's unpublished research and printed in George Steevens's edition of the plays (Shakespeare 1778, 269-346). Most of Malone's evidence was external--in particular, allusions to the plays by others--but he identified one kind of internal evidence: Shakespeare "in his early plays appears to have been much addicted to rhyming" (Shakespeare 1778, 288). Malone thought this a useful general guide to chronology but not infallible, since the Henry 6 plays have few rhymes despite being early (Shakespeare 1778, 280n). Although many of Malone's datings are now considered wildly inaccurate--he put Twelfth Night in 1614 and The Winter's Tale in 1594--his dating of The Two Gentlemen of Verona to 1593 is well within today's investigators' sense of the reasonable limits.

At this point, Malone believed The Two Gentlemen of Verona to have been written after Titus Andronicus (1589), Love's Labour's Lost (1591), the three Henry 6 plays (1591-92), and Pericles (1592). Malone later revised his chronology so that The Two Gentlemen of Verona was Shakespeare's first play and written in 1591 (Shakespeare 1821, 7). Yet the idea that The Two Gentlemen of Verona is early Shakespeare had long been the critical orthodoxy. Half a century before Malone's chronology was published, Alexander Pope referred to the play being "suppos'd to be one of the first he wrote" (Shakespeare 1725, 155). The earliness of The Two Gentlemen of Verona was established to the satisfaction of most eighteenth-century editors by its inexpert handling of language and dramatic action. Pope thought its style to be "less figurative, and more natural and unaffected" (Shakespeare 1725, 155n) than Shakespeare's other works, which quality he found at odds with the supposed early date. The second half of the opening scene comprising an exchange of puns between Proteus and Speed was counted by Pope as its second scene and one "compos'd of the lowest and most trifling conceits" whose existence could be explained only by Shakespeare's pandering to the "gross taste of the age he liv'd in" (Shakespeare 1725, 157n). Pope mentioned in passing that certain scenes in Shakespeare's plays were interpolated by their first actors, but did not make that claim for this scene or its play.

Lewis Theobald reprinted Pope's opinion about the play's natural, unaffected style and added only that it is "One of his very worst" albeit rather accurately printed in the 1623 Folio (Shakespeare 1733, 153n). William Warburton too reprinted Pope's note about the natural style and made no further comment (Shakespeare 1747, 175n). Samuel Johnson approved Pope's opinion about the natural style and guessed that the play was well printed because it was unsuccessful on the stage, hence little played and "less exposed to the hazards of transcription" (Shakespeare 1765, 179n). Regarding the second half of the opening scene, Johnson agreed with Pope that it is "mean and vulgar" but disputed his claim that it was "interpolated by the players", which claim Pope had not in fact made (Shakespeare 1765, 183n). Malone later made the same misreading of Pope's claim (Shakespeare 1821, 13). Edward Capell reprinted Pope's note and objected that far from being at odds with its early date the play's lack of figurative language, its "simpleness (or more properly) tameness", was thereby explained: only later did Shakespeare develop "a diction more animated, and numbers [that is, prosody] of more variety" (Shakespeare 1768, 3n).

Of the major eighteenth-century editors of Shakespeare, Thomas Hanmer alone took the view that The Two Gentlemen of Verona is someone else's play to which Shakespeare added only "some speeches and lines thrown in here and there, which are easily distinguish'd, as being of a different stamp from the rest" (Shakespeare 1744, 143n). In his book of Critical Observations John Upton dismissed The Two Gentlemen of Verona as self-evidently not Shakespeare's work, "if any proof can be formed from manner and style" (Upton 1746, 274). Upton gave no examples. Hanmer offered just one illustration of his claim of inauthenticity: the final-scene speech in which Valentine gives all that was his "in Silvia" to Proteus. Hanmer thought it "impossible" that Shakespeare "could make Valentine act and speak so much out of character; or give to Silvia so unnatural a behaviour as to take no notice of this strange declaration if it had been made" (Shakespeare 1744, 208n). This declaration has troubled critics ever since.

For the first Arden Shakespeare edition, R. Warwick Bond solved the problem of Valentine's final-scene declaration by invoking an idea he attributed to "Dr. Batteson" (Shakespeare 1906, xxxvi-xxxviii). When Valentine says "And that my love may appear plain and free, | All that was mine in Silvia I give thee" he transfers to Proteus not his lady but his love for the lady. Bond neglected to observe that this requires Valentine's love to be a finite, measurable good (hence "All") and yet simultaneously an infinite, unmeasurable good, else Proteus's gain is Silvia's loss. In defence of the Batteson-Bond claim one might note that Shakespeare repeatedly returned to paradoxes arising from the dual finity and infinity of love, as in "There's beggary in the love that can be reckoned" (Antony and Cleopatra 1.1.15) and "The more [love] I give to thee | The more I have, for both are infinite" (Romeo and Juliet 2.1.176-772).

In the late-nineteenth century, the stratification hypothesis was deployed with and without a supposed second writer in order to explain the problems of logic and geography in The Two Gentlemen of Verona. Largely on the basis of metrical variation, F. G. Fleay argued that acts 1 and 2 were written by Shakespeare in 1593-94 and then composition was broken off while other plays were written and Shakespeare returned to finish the play by writing acts 3, 4 and 5 in 1595 (Fleay 1875, 289). In his Shakespeare Manual Fleay repeated this claim, although with acts 1 and 2 completed at "the beginning of 1593" (Fleay 1876, 28), and he asserted it again in his Chronicle History of the Life and Work of William Shakespeare, although this time hedging his bets by finding signs of the first stratum in scene 1.3 (Fleay 1886, 188-91). Surveying Fleay's work, and Gregor Sarrazin's arguments from vocabulary that bolstered it (Sarrazin 1896, 163), Bond saw "much in this idea of the present as a revised form of the play" (Shakespeare 1906, xi) and welcomed Fleay's abandonment of his original conviction (Fleay 1875, 303-04; Fleay 1876, 27) that one of the strata is not by Shakespeare. Bond found in the play's metrical irregularity "support [for] a later working-over of the piece" (Shakespeare 1906, xiv) but did not spell out why working-over would produce it.

Editing the play for Cambridge University Press's New Shakespeare series, Arthur Quiller-Couch and John Dover Wilson supported the stratification theory and revived the idea that one of the strata was not written by Shakespeare. Quiller-Couch's introduction referred to the hands of one or more "botchers" of the play upon whom we should lay the blame for Sir Eglamour's final-scene abandoning of Silvia, Valentine's giving her to Proteus and Julia's consequential swoon (Shakespeare 1921, xvi). Providing the detail on which this claim was based, Wilson's study of "The Copy" (Shakespeare 1921, 77-82) found evidence of bodged cutting in 2.4, 3.2, 4.1 and 5.4. Scenes 2.2 and 5.3 Wilson thought merely the surviving ends of what were originally longer scenes, patched at their beginnings with a few lines of prose to cover the cuts. Moreover, there used to be a scene between what are now the lines 3.1.187 and 3.1.188, there used to be a scene between what are now scenes 4.3 and 4.4, and 4.4 had something cut from its middle, to judge from its abrupt jump in the action.

Wherever these cuts occur, argued Wilson, we must assume the presence of patching lines by someone other than Shakespeare. In addition to the scenes already identified, Wilson diagnosed cutting and patching in 1.2, 1.3 and 2.5, and he reckoned all of Speed's part and the whole of 2.5 to be non-Shakespearian. Putting those segments together we get the following locations for non-Shakespearian matter: 1.1.70-146, 1.2, 1.3, 2.1, 2.2, 2.4, 2.5, 3.1, 3.2, 4.1, 4.4, 5.3 and 5.4. This amounts to around three-quarters of the play, which is rather too much to be tested by the methods used below to detect internal inconsistency. If we exclude those parts where Wilson supposed only light interference--not easily determined as his phrasing is vague and ambiguous--we find 1.1.70-146, 2.1, 2.5, 3.1.276-372 and 5.4 to be potentially non-Shakespearian. This amounts to only around 4,200 words, which is rather too little for our method.

Subsequent studies of The Two Gentlemen of Verona confirmed the stratification hypothesis. J. M. Robertson revived Hanmer's view that the play is essentially non-Shakspearian, thinking it primarily Robert Greene's work that Shakespeare revised, most heavily at the beginning, with George Peele and Thomas Nashe also making contributions (Robertson 1923, 1-44). Robertson found the verse of The Two Gentlemen of Verona vastly inferior to the rest of Shakespeare and denied that earliness explained this fault: in dedicating the more accomplished Venus and Adonis to the Earl of Southampton, Shakespeare placed it at the beginning of his career as the "first heire of my inuention" (Shakespeare 1593, [A]2r). Moreover, if genuine and early, the play's high proportion of feminine endings requires that in subsequent plays Shakespeare curtailed this prosodic habit only to increase it again later. For Robertson the necessity that we find "in artistic growth as in other organic phenomena a process of evolution" (Robertson 1923, 18) ruled out such a fall-and-rise. Once Shakespeare was eliminated as the author of The Two Gentlemen of Verona, Greene emerged as the frontrunner because his works share its words, phrases, and metronomic prosody.

George B. Parks revived the idea of sole-author stratification with the play's problems attributed to its being written first as a story taking place in one Italian city and then being altered to introduce the many journeys and their attendant confusions of location. The alterations introduced five new scenes, 1.3, 2.2, 2.3, 2.7 and 4.4, and inserted 127 new lines into four more, 1.1, 4.2, 5.2 and 5.4 (Parks 1937, 8). This amounts to under a quarter of the play as we have it, too little to be tested by our method. Samuel A. Tannenbaum agreed that only Shakespeare wrote the play and dated the stratum of authorial revision to 1598, when one of the sources first appeared in print in English (Tannenbaum 1939). This last study has not yet been consulted by the present author and its contents are merely reported second-hand.

R. Warwick Bond's successor as editor of the Arden Shakespeare The Two Gentlemen of Verona was Clifford Leech, and after surveying the stratification hypotheses of others discussed above (Shakespeare 1969a, 22-26) he offered his own (Shakespeare 1969a, 26-31), which he frankly admitted being unable to convince his general editor, Harold F. Brooks, to accept. According to Leech's theory, the parts written later than the rest of the play are all of Lance's role (2.3, 2.5, 3.1.260-372 and 4.4.1-59) plus scenes 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 2.2, 2.6 and 2.7. Leech did not claim that the play existed in two versions: rather, it was not finished--it was still in composition--until the second layer was added. The strata were, however, written at different times: 1592 for the first layer and late 1593 for the second (Shakespeare 1969a, 35). Leech's strata we can test using Burrow's Zeta method, and this is carried out below.

Aside from Quiller-Couch & Wilson's and Leech's, all the major twentieth and twenty-first century editions of the play rejected stratification and instead used one or both of the arguments that i) the text's problems arise from Shakespeare's inexperience as a dramatist, and ii) in Shakespeare's time things that disturb us--especially regarding gender relations and the dominance of male-male relationships over all others--were simply unremarkable (Shakespeare 1935, vii-xv; Shakespeare 1964, xxiii-xl; Shakespeare 1968, 7-40; Shakespeare 1969b, 72-75; Wells et al. 1987, 166; Shakespeare 1990, 1-50, 141-152; Shakespeare 1997, 77-83; Shakespeare 1999, xiii-lv; Shakespeare 2002, 111-14; Shakespeare 2004, 116-30; Shakespeare 2007, 52-55; Shakespeare 2008, 1-62). Only M. R. Ridley laid out Quiller-Couch & Wilson's stratification theory at any length and he was sceptical except regarding the final scene, where he was half persuaded (Shakespeare 1935, xiii-xiv). William C. Carroll found Leech's claim that Lance's part was a late interpolation into the play to be the least unconvincing part of his stratification theory (Shakespeare 2004, 126-27). Argument (i) has drawn considerable strength from Stanley Wells's sensitive and eloquent account of weaknesses in the play's dramaturgy (Wells 1963).

Looking for Stratification using the Zeta Test

We can approach the topic of the alleged stratification of The Two Gentlemen of Verona using the Zeta word-counting test devised by John Burrows and refined and implemented in software by Hugh Craig as the Intelligent Archive (Burrows 2007; Craig & Kinney 2009; Craig & Whipp 2010). The test works by deriving from a pair of electronic texts, called the Base and the Counter, the words whose frequencies of use most distinguish those texts. That is, the test counts the frequencies of all the words present and selects those that are most frequently used in the Base and least frequently used in the Counter (thus, words characteristic of Base) and conversely the words that are least frequently used in the Base and most frequently used in the Counter (thus, words characteristic of the Counter). Once these sets of characteristic marker words are known, their frequencies can be counted in a candidate text to see if it is more like the Base or the Counter in its rates of using them. Typically, the Base and Counter will be texts securely attributed to different authors, the candidate a text of unknown authorship, and the candidate's sharing of word preferences with Base or Counter is presented as evidence for authorship by the same person.

To illustrate the method for investigating whether the alleged stratification of The Two Gentlemen of Verona has a corollary in the play's word choices we can first make an arbitrary division of a text of the play into two halves: the first half (by word-count) we will designate part A and the second part B. (This happens to correspond very roughly to Fleay's initial claim discussed above that the play has two strata: acts 1 and 2 versus acts 3, 4 and 5.) These halves contain around 8,000 words each and we may compare one with the other by looking for the top 200 words that each half favours and the other half disfavours.3 If A is distinct from B in its word choices, then any part A should be more like the rest of A in its frequencies of word usages than it is like the whole of B, and any part of B should be more like the rest of B than it is the whole of A. To test this, we divide A into four parts, A1, A2, A3 and A4, comprising the first, second, third and fourth 2,000-word segments of A. Likewise for B divided into B1, B2, B3 and B4. Then we set A1 and B1 aside and use A2+A3+A4 as our Base and B2+B3+B4 as our Counter, from which Zeta produces a set of words that are significantly more common in A2+A3+A4 than they are in B2+B3+B4. These marker words are then counted in A1 and B1 to see if each of these segments is more like A or B generally. If A is generally different from B--as the stratification hypothesis requires--then we would expect A1 to be more like A2+A3+A4 than B1 is like A2+A3+A4. We repeat the process with B2+B3+B4 as our Base and A2+A3+A4 as our Counter, which produces a list of marker words that the B segments favour. Again, If A is generally different from B--the stratification hypothesis--then we would expect A1 to be less like B2+B3+B4 than B1 is like B2+B3+B4.

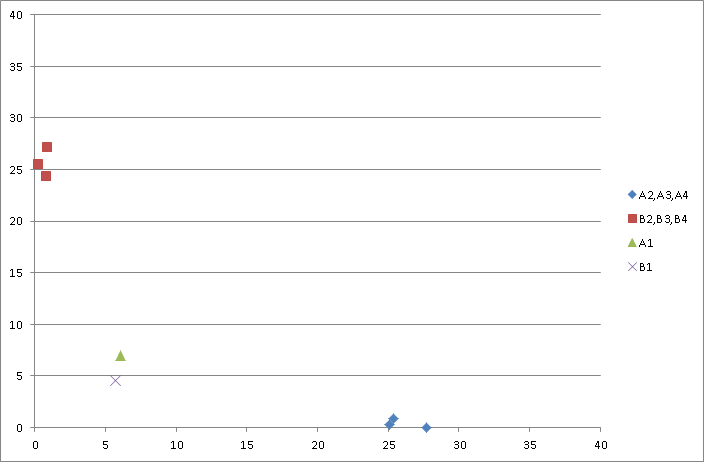

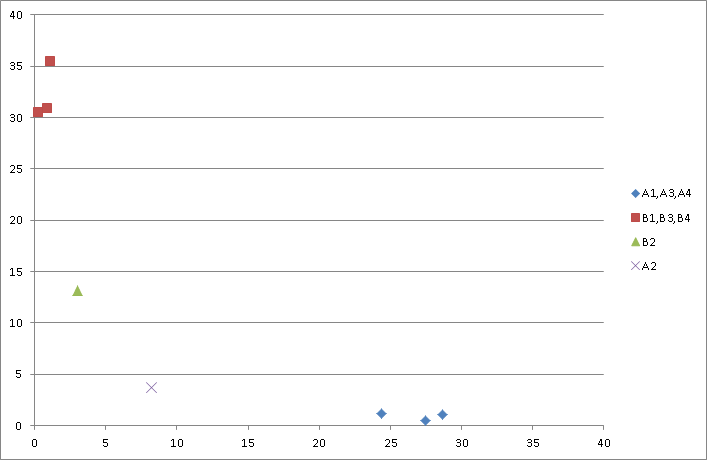

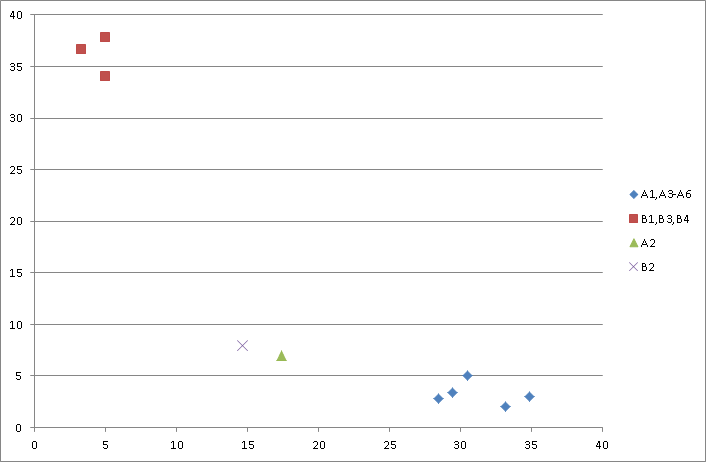

Figure One plots the result for the first of these tests4. The x-axis shows each segment's frequency of use of words characteristic of A2+A3+A4 (taken as a group) and the y-axis shows each segment's frequency of use of words characteristic of B2+B3+B4 (taken as a group). The frequencies are calculated by dividing the segment's number of occurrences of the 200 marker words by the number of word types in the segment and multiplying by 100 to give a percentage. Thus in Figure One, around a quarter of the word-types in each of the segments A2, A3 and A4 are words from the list of 200 A-characteristic marker words and almost none are B-characteristic marker words, and likewise around a quarter of the word-types in segments B2, B3 and B4 are words from the list of 200 B-characteristic marker words and almost none are A-characteristic marker words. This clustering in the bottom right and top left corners of the plot is what we would expect because we went looking for precisely the words that would create such clustering, being the words that are distinctive of each half of the play. This does not tell us that the two halves of the play are significantly distinct from one another, since we have deliberately excluded all the words they use equally frequently.

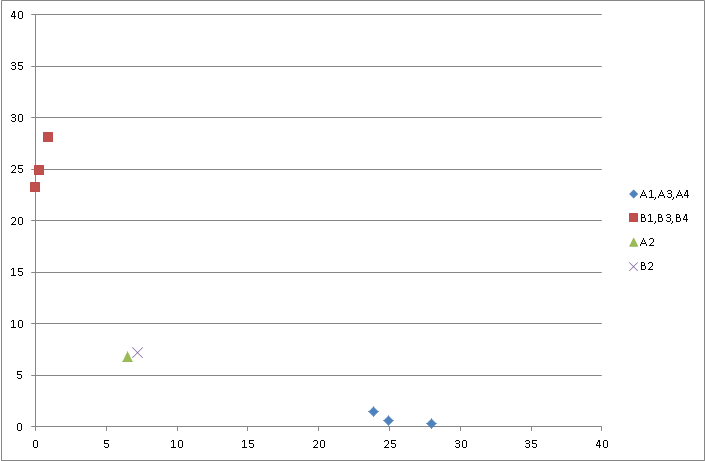

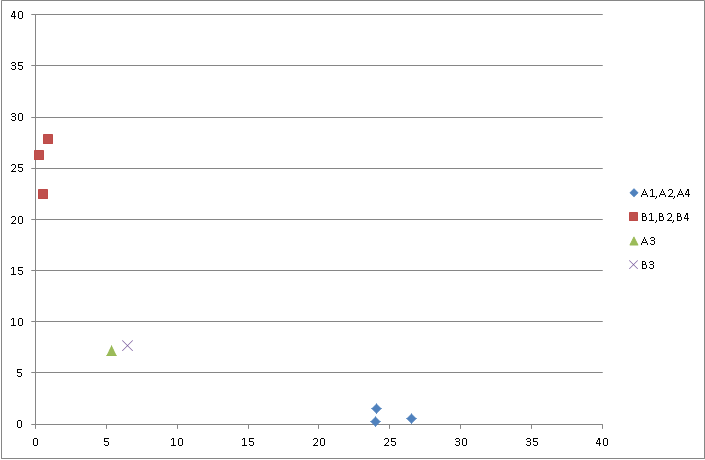

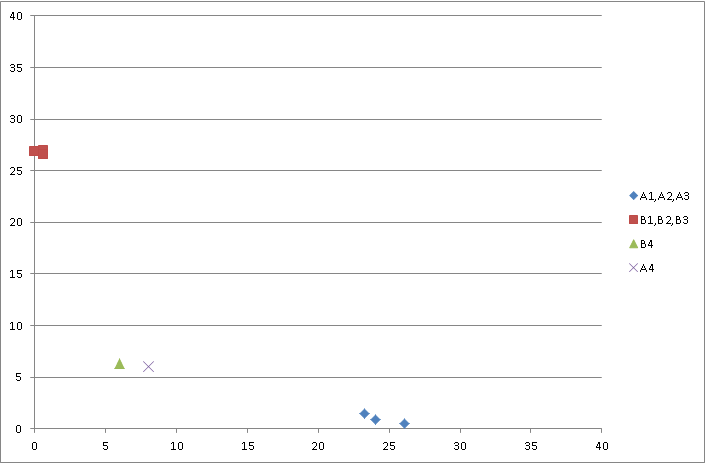

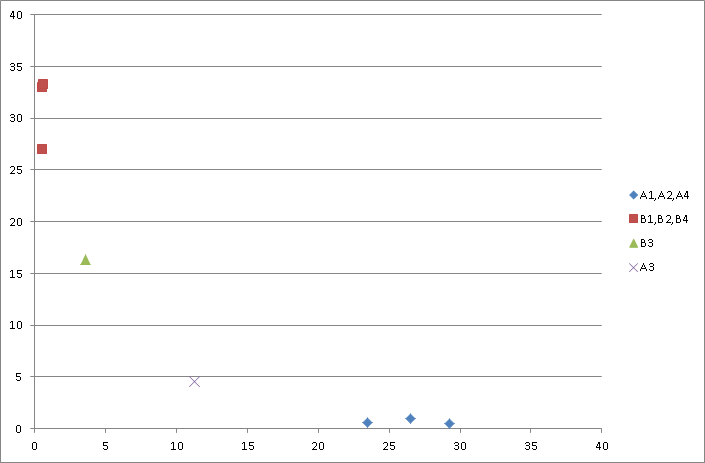

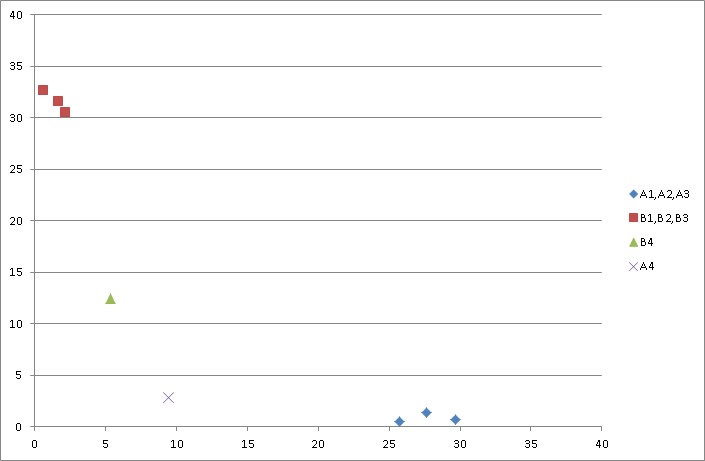

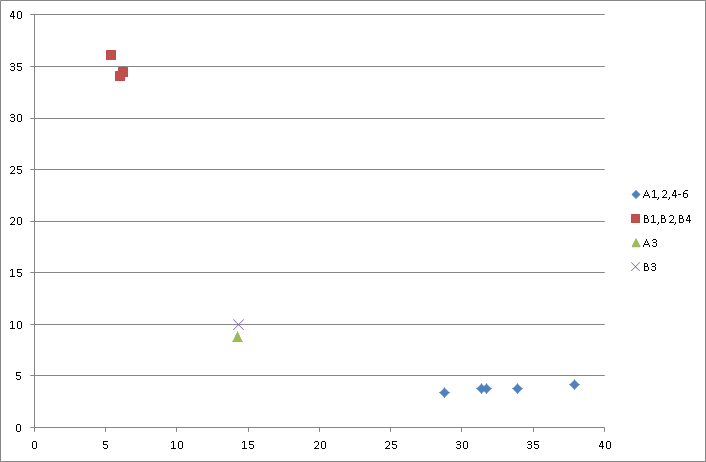

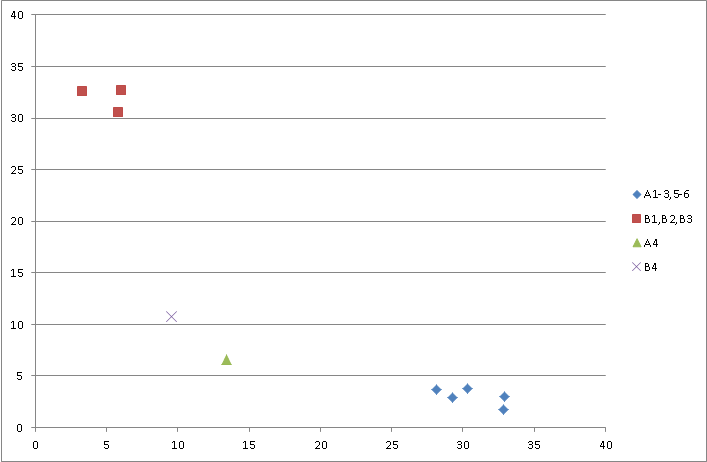

The crucial matter is how frequently the segments A1 and B2 use these words. If the play really divides into two halves, we would expect A1 and B2 to differ in their rates of usage of words characteristic of the half from which they came. That is, A1 should fall nearer to the A2+A3+A4 cluster (because it shares their word preferences) than the B2+B3+B4 cluster, and B1 should fall nearer to the B2+B3+B4 cluster (because it shares their word preferences) than the A2+A3+A4 cluster. This is not what we find: A1 and B1 are roughly equidistant from the two clusters. Figures Two, Three, and Four show that we get the same results when we repeat the tests for A2 and B2 tested against the remainder of their halves (A1+A3+A4 and B1+B3+B4), and so on for A3 and B3 and A4 and B4. That is to say, each eighth of the play in the first half scores like its corresponding eighth in the second half on its frequencies of words characteristic of the rest of the first half, and the same is true for each eighth in the second half.

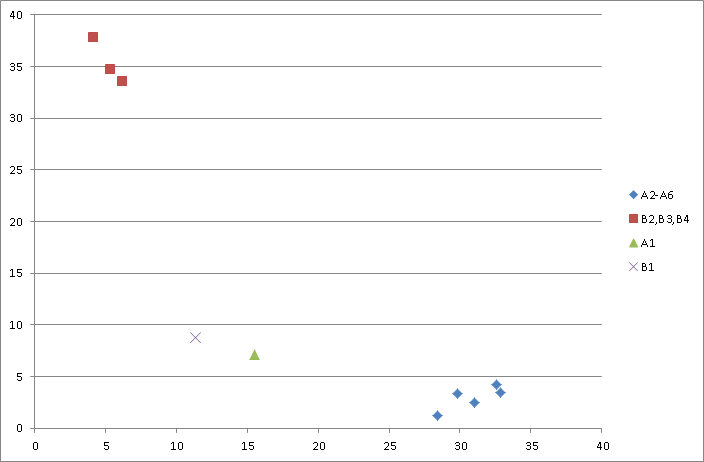

What would we expect these graphs to look like--how far apart would the two tested segments be--if the play really were stratified? To find out, we can run the tests on a fabricated pseudo-text that is genuinely made of disparate halves written by different authors at different times. For this purpose we took as part A the first half of John Lyly's play Sappho and Phao (first performed around 1583) and as part B the second half of John Fletcher's play Rule a Wife and Have a Wife (first performed in 1624). Again A was divided into four quarters, A1 to A4, and B likewise into B1 to B4. Again the search was for the 200 marker words for each half and the software was instructed to treat variant spellings of a word as if they were the same. Figures Five, Six, Seven and Eight show how this intentionally stratified text fared in the Zeta test, and as can be seen the isolated segments A1, A2, A3 and A4 each fell closer to the rest of A than they did B and each of the isolated segments B1, B2, B3 and B4 fell closer to the rest of B than they did A. Without processing the results further, this visualization of the word frequencies confirms that parts A and B constitute distinct strata when considered in terms of their word choices.

Leech's proposed stratification of The Two Gentlemen of Verona designates the original writing, which we will call part A, as 2.1, 2.4, 3.1.1-259, 3.2, 4.1, 4.2, 4.3, 4.4.60-202, 5.1, 5.2, 5.3 and 5.4, totalling 10,556 words, and the later writing, our part B, as 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 2.2, 2.3, 2.5, 2.6, 2.7, 3.1.260-372 and 4.4.1-59, totalling 6,499 words. (Line references here are keyed to Shakespeare 1989; textual and line-referencing variations between editions are for this play negligible.) Rather than using 2,000-word segments, these strata suggest use of 1,625-word segments, with part A having six such segments, A1-A6 (and we throw away the last 806 words), and part B having four such segments, B1-B4, the last of which is one word short. We could eliminate the differences in the size of A and B by discarding segments A5 and A6 altogether, but in fact there is no harm in allowing these to contribute to the lists of marker words that distinguish parts A and B. We will in any case test only how A1-A4 compare to B1-B4, to preserve parity with the preceding tests that established our expections regarding segments' clustering in the event of a play truly being made of disparate strata.

Figures Nine, Ten, Eleven and Twelve show how the segment pairs A1-B1, A2-B2, A3-B3 and A4-B4 fall on graphs that show on the x-axis each segment's count of marker words favoured by part A and on the y-axis each segment's count of marker words favoured by part B. As before, and as expected, segments from part A score highly on A-favoured words (high x) and lowly on B-favoured words (low y) and segments from part B score lowly on A-favoured words (low x) and highly on B-favoured words (high y). The scores of the segment pairs A1-B1 and A4-B4 are noticeably unlike those arising when we arbitrarily divided our play into first-half and second-half strata (Figures One, Two, Three and Four) and similar to the scores achieved when we created a strongly stratified pseudo-text made of the front half of Lyly's Sappho and Phao and the back half of Fletcher's Rule a Wife and Have a Wife (Figures Five, Six, Seven and Eight). For these pairs, the segments are, as it were, 'attracted' towards their home strata. On this evidence, there appear to be grounds for supposing that Leech's proposed stratification of the play does indeed reflect differences in word preferences in different parts of the play. The differences are analogous to, although less extreme than, those found in the stratification of an authorially hybrid play. Further investigation of the authorship of The Two Gentlemen of Verona is warranted.

Figures

Figure One The Two Gentlemen of Verona divided into first (A) and second (B) half, each half divided into four 2,000-word segments. The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A2+A3+A4 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B2+B3+B4.

Figure Two The Two Gentlemen of Verona divided into first (A) and second (B) half, each half divided into four 2,000-word segments. The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A1+A3+A4 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B1+B3+B4.

Figure Three The Two Gentlemen of Verona divided into first (A) and second (B) half, each half divided into four 2,000-word segments. The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A1+A2+A4 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B1+B2+B4.

Figure Four The Two Gentlemen of Verona divided into first (A) and second (B) half, each half divided into four 2,000-word segments. The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A1+A2+A3 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B1+B2+B3.

Figure Five The first half of Sapho and Phao (part A) and the second half of Rule a Wife and Have a Wife (part B), each part divided into four 2,000-word segments. The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A2+A3+A4 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B2+B3+B4.

Figure Six The first half of Sapho and Phao (part A) and the second half of Rule a Wife and Have a Wife (part B), each part divided into four 2,000-word segments. The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A1+A3+A4 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B1+B3+B4.

Figure Seven The first half of Sapho and Phao (part A) and the second half of Rule a Wife and Have a Wife (part B), each part divided into four 2,000-word segments. The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A1+A2+A4 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B1+B2+B4.

Figure Eight The first half of Sapho and Phao (part A) and the second half of Rule a Wife and Have a Wife (part B), each part divided into four 2,000-word segments. The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A1+A2+A3 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B1+B2+B3.

Figure Nine The Two Gentlemen of Verona divided into Leech's proposed first stratum (part A) and second stratum (part B), each part divided into 1,625-word segments (6 segments for part A, 4 segments for part B). The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A2+A3+A4+A5+A6 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B2+B3+B4.

Figure Ten The Two Gentlemen of Verona divided into Leech's proposed first stratum (part A) and second stratum (part B), each part divided into 1,625-word segments (6 segments for part A, 4 segments for part B). The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A1+A3+A4+A5+A6 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B1+B3+B4.

Figure Eleven The Two Gentlemen of Verona divided into Leech's proposed first stratum (part A) and second stratum (part B), each part divided into 1,625-word segments (6 segments for part A, 4 segments for part B). The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A1+A2+A4+A5+A6 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B1+B2+B4.

Figure Twelve The Two Gentlemen of Verona divided into Leech's proposed first stratum (part A) and second stratum (part B), each part divided into 1,625-word segments (6 segments for part A, 4 segments for part B). The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A1+A2+A3+A5+A6 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B1+B2+B3.

Notes

Works Cited

1The prose of this essay is Egan's; Hirsch suggested the method and taught Egan how to perform it using the Intelligent Archive software.

2 Where the source of a Shakespeare quotation is not stated, the wording and line-references derive from the electronic edition of the Oxford Complete Works (Shakespeare 1989); other edition's variations from this edition's wording and line-counting will be noted where necessary.

3 Stratification created by authorial revision of parts of a play is unlikely to produce significant differences in the spellings of particular words because most writer's spelling habits change relatively slowly, and the subsequent imposition of scribal and compositorial spelling preferences are in this case likely to swamp any such authorial drift. Thus for our purposes all spellings of one word should count equally as a use of that word. The Intelligent Archive software is able to normalize spellings where (as in this case) the input text explicitly lemmatizes such variations and additionally to apply its own rules of normalization arising from substantial research on algorithmic methods for doing so (Craig & Whipp 2010). The text used here was an XML-encoded transcription of the 1623 Folio edition conforming to the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) schema, supplied with the Intelligent Archive software provided by its author Hugh Craig. The Intelligent Archive's normalization of spelling was switched on for these experiments.

4The twelve Microsoft Excel spreadsheets containing the results of the twelve experiments described here (leading to Figures One to Twelve) are available for download from http://gabrielegan.com/scratch/paris450. In each spreadsheet document, Sheet 1 contains the 200 marker words for the part A segments, Sheet 2 contains the 200 marker words for the part B segments, and Sheet 3 contains the summary data and the scatter-plots derived from them.

Burrows, John. 2007. "All the Way Through: Testing for Authorship in Different Frequency Strata." Literary and Linguistic Computing 22. 27-47.

Craig, Hugh and Arthur F. Kinney. 2009. Shakespeare, Computers, and the Mystery of Authorship. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press.

Craig, Hugh and R. Whipp. 2010. "Old Spellings, New Methods: Automated Procedures for Indeterminate Linguistic Data." Literary and Linguistic Computing 25. 37-52.

Fleay, F. G. 1875. "On Certain Plays of Shakspere of Which Portions Were Written at Different Periods of His Life." Transactions of the New Shakspere Society Number 2. 285-317.

Fleay, F. G. 1876. Shakespeare Manual. London. Macmillan.

Fleay, F. G. 1886. A Chronicle History of the Life and Work of William Shakespeare: Player, Poet, and Playmaker. London. John C. Nimmo.

Parks, George B. 1937. "The Development of The Two Gentlemen of Verona." Huntington Library Bulletin 11. 1-11.

Robertson, J. M. 1923. The Shakespeare Canon. Vol. 2: The Two Gentlemen of Verona; Richard II; The Comedy of Errors; Measure for Measure. 5 vols. London. Routledge.

Sarrazin, Gregor. 1896. "Zur Chronologie Von Shakespeare's Dichtungen." Shakespeare Jahrbuch 32. 149-81.

Shakespeare, William. 1593. Venus and Adonis. STC 22354. London. Richard Field.

Shakespeare, William. 1725. The Works. Ed. Alexander Pope. Vol. 1: Preface; The Tempest; A Midsummer Night's Dream; The Two Gentlemen of Verona; The Merry Wives of Windsor; Measure for Measure; The Comedy of Errors; Much Ado About Nothing. 6 vols. London. Jacob Tonson.

Shakespeare, William. 1733. The Works. Ed. Lewis Theobald. Vol. 1: Preface; The Tempest; The Midsummer-Night's Dream; The Two Gentlemen of Verona; Merry Wives of Windsor; Measure for Measure; Much Ado About Nothing. 7 vols. London. A. Bettesworth, C. Hitch, J. Tonson, F. Clay, W. Feales, and R. Wellington.

Shakespeare, William. 1744. The Works. Ed. Thomas Hanmer. Vol. 1: The Tempest, A Midsummer Night's Dream, The Two Gentlemen of Verona, The Merry Wives of Windsor, Measure for Measure, The Comedy of Errors, Much Ado About Nothing. 6 vols. Oxford. The Theatre.

Shakespeare, William. 1747. The Works of Shakespear. Ed. William Warburton. Vol. 1: The Tempest; A Midsummer-Night's Dream; The Two Gentlemen of Verona; The Merry Wives of Windsor; Measure for Measure. 8 vols. London. J. and P. Knapton and S. Birt.

Shakespeare, William. 1765. The Plays. Ed. Samuel Johnson. Vol. 1: Preliminary Matter; The Tempest; A Midsummer-Night's Dream; The Two Gentlemen of Verona; Measure for Measure; The Merchant of Venice. 8 vols. London. J. and R. Tonson [etc.].

Shakespeare, William. 1768. Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies. Ed. Edward Capell. Vol. 1: Introduction; The Tempest; The Two Gentlemen of Verona; The Merry Wives of Windsor. 10 vols. London. Dryden Leach for J. and R. Tonson.

Shakespeare, William. 1778. The Plays. Ed. George Steevens. Vol. 1: Prefaces; The Tempest; The Two Gentlemen of Verona; The Merry Wives of Windsor. 10 vols. London. C. Bathurst [and] W. Strahan [etc.].

Shakespeare, William. 1821. The Plays and Poems. Ed. Edmond Malone and James Boswell. Vol. 4: Two Gentlemen of Verona; Comedy of Errors; Love's Labour's Lost. 21 vols. London. F. C. and Rivington [etc.].

Shakespeare, William. 1906. The Two Gentlemen of Verona. Ed. R. Warwick Bond. The Arden Shakespeare. London. Methuen.

Shakespeare, William. 1921. The Two Gentlemen of Verona. Ed. Arthur Quiller-Couch and John Dover Wilson. The New Shakespeare. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press.

Shakespeare, William. 1935. The Two Gentlemen of Verona. Ed. M. R. Ridley. The New Temple Shakespeare. London. J. M. Dent.

Shakespeare, William. 1964. The Two Gentlemen of Verona. Ed. Bertrand Evans. The Signet Classic Shakespeare. New York. New American Library.

Shakespeare, William. 1968. The Two Gentlemen of Verona. Ed. Norman Sanders. New Penguin Shakespeare. Harmondsworth. Penguin.

Shakespeare, William. 1969a. The Two Gentlemen of Verona. Ed. Clifford Leech. The Arden Shakespeare. London. Methuen.

Shakespeare, William. 1969b. The Complete Pelican Shakespeare: The Comedies and Romances. General editor Alfred Harbage. 3 vols. Harmondsworth. Penguin.

Shakespeare, William. 1989. The Complete Works. Ed. Stanley Wells, Gary Taylor, John Jowett, and William Montgomery. Electronic edition prepared by William Montgomery and Lou Burnard. Oxford. Oxford University Press.

Shakespeare, William. 1990. The Two Gentlemen of Verona. Ed. Kurt Schlueter. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press.

Shakespeare, William. 1997. The Norton Shakespeare Based on the Oxford Shakespeare. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt, Walter Cohen, Jean E. Howard, and Katharine Eisaman Maus. New York. W. W. Norton.

Shakespeare, William. 1999. The Two Gentlemen of Verona. Ed. Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstine. The New Folger Library Shakespeare. New York. Washington Square Press.

Shakespeare, William. 2002. The Complete Works (The New Pelican Text). Ed. Stephen Orgel and A. R. Braunmuller. New York. Penguin.

Shakespeare, William. 2004. Two Gentlemen of Verona. Ed. William C. Carroll. The Arden Shakespeare. London. Thomson Learning.

Shakespeare, William. 2007. The Complete Works (=The Royal Shakespeare Company Complete Works). Ed. Jonathan Bate and Eric Rasmussen. Basingstoke. Macmillan.

Shakespeare, William. 2008. The Two Gentlemen of Verona. Ed. Roger Warren. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford. Oxford University Press.

Tannenbaum, Samuel A. 1939. The New Cambridge Shakespeare and The Two Gentlemen of Verona. New York. Tenny.

Upton, John. 1746. Critical Observations on Shakespeare. London. G. Hawkins.

Wells, Stanley, Gary Taylor, John Jowett and William Montgomery. 1987. William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. Oxford. Oxford University Press.

Wells, Stanley. 1963. "The Failure of The Two Gentlemen of Verona." Shakespeare Jahrbuch 99. 161-73.