"'The like to Protheus': Lance versus Speed as two conceptions of the clown in early Shakespeare" by Gabriel Egan

The character of Lance in Shakespeare's The Two Gentlemen of Verona is noticeably detachable from the story. He appears in just four scenes (2.3, 2.5, 3.1 and 4.4) and thus is absent from scenes for which the dramatic logic suggests he ought to be present. The scenes of absence include the opening scene where his master Proteus borrows Valentine's servant Speed to deliver a letter to Julia, the final scene where Lance fails to accompany Proteus into the forest in pursuit of Silvia, and almost all the intervening scenes of Proteus attending the court of the Duke of Milan. The Folio's dramatis personae for The Two Gentlemen of Verona asserts that Speed is "a clownish seruant" to Valentine and Lance is "the like to Protheus" (Shakespeare 1623, D1v), and as we shall see that is in some ways true: they share characteristics. These might arise, however, not from Shakespeare having one type of 'clown' in mind and giving its characteristics to two men, but instead from rewriting that added Lance after the majority of the play had been composed and that gave him some of Speed's existing lines.

The following table summarizes the two characters' appearances in the play from their entrances and exits1:

Speed (Valentine's man) Lance (Proteus's man) On 1.1.69 Off 1.1.140 On 2.1.0 Off 2.1.165 On 2.3.0 Off 2.3.58 On 2.5.0 On 2.5.0 Off 2.5.51 Off 2.5.51 On 3.1.187 On 3.1.275 Off 3.1.369 Off 3.1.372 On 4.1.2 Off 4.1.74 On 4.4.0 Off 4.4.59

As we can see, Speed and Lance are onstage together just twice: for all of the short scene 2.5 where the former, who arrived there first, welcomes the latter to Milan, and in the last quarter of 3.1 where they perform a double act in evaluating a record of the virtues and vices of a milkmaid. In all, Lance's appearances in four scenes contain a surprisingly large number of substantial soliloquies for a minor character--three of them (2.3.1-32, 3.1.260-75 and 4.4.1-38)--if we do not count his dog Crab as another character. For these reasons, editors have long wondered whether the script contains the writings of hands other than Shakespeare's, and whether Shakespeare made alterations after the play's first composition.

John Dover Wilson thought that the various problems with the text of The Two Gentlemen of Verona, including the oft-commented upon discontinuities of place, plot and action, were the result of non-authorial botching:

Adaptation for a particular company might carry with it alterations to fit a new cast. Now there are two clowns in this text, and the difference in their quality is striking, to say the least of it. Launce is humorous, in the true Shakespearian manner, and his sallies, some of which we have been able to restore, bite almost every time. But Speed is a poor stick, without character, and he has not a single witty thing to say from beginning to end. In short, we think that Speed may be the creation or re-creation of the adapter . . . (Shakespeare 1921, 81).

Thus, according to Wilson, the character of Speed was a later addition to the script. Wilson's view that Speed has nothing witty to say is difficult to understand since the character is clearly the first in a line of Shakespearian quibblers leading to Feste in Twelfth Night and the Fool in King Lear. Typical of Speed in this regard is:

PROTEUS Beshrew me but you have a quick wit.

SPEED And yet it cannot overtake your slow purse.

PROTEUS Come, come, open the matter in brief. What said she?

SPEED Open your purse, that the money and the matter

may be both at once delivered.

(The Two Gentlemen of Verona 1.1.121-26)

If Wilson is right that Speed is an adapter's work then this person was remarkably like Shakespeare in his wit, although Wilson cannot see this: "there is nothing in it, nothing at all" (Shakespeare 1921, 82).

Editing the play for the second series of the Arden Shakespeare, Clifford Leech reversed Wilson's logic and argued that Lance was a late addition, judging from how little he is embedded in the play's action (Shakespeare 1969, 22-35). The insertion of Lance was, according to Leech, the third part of a four-stage evolution in the play's composition, during which the plot changed radically to introduce the journeying from Verona to Milan. Certainly the whole of 2.3--comprising Lance's soliloquy introducing his dog Crab followed by 26 lines of dispensable comic interaction with the servant Panthino sent to hurry him aboard ship--could be cut without harm to the action. Likewise, the whole of 2.5, Lance being welcomed to Milan by Speed, could be removed without damage. Lance's contribution to 4.4 is its opening soliloquy about Crab's failure to behave as an acceptable gift--"I was sent to deliver him as a present to Mistress Silvia from my master" (4.4.6-8)--and then 16 lines of interaction with Proteus that have in any case come under suspicion because they contradict the preceding soliloquy: Crab, we learn, was not the intended present. All this too could easily be detached.

That just leaves Lance's role in 3.1, which is the only time Lance is without his dog and, apart from the 16 lines in 4.4 just discussed, the only time we see him serving his master Proteus. Moreover, as Leech notes (Shakespeare 1969, 27), Lance in 3.1 sounds surprising like Speed, mirroring the deliberately quibbling mistakings that Speed displays in his interactions with Valentine:

LANCE . . . There's not a hair on 's head but 'tis a Valentine.

PROTEUS Valentine?

VALENTINE No.

PROTEUS Who then--his spirit?

VALENTINE Neither.

PROTEUS What then?

VALENTINE Nothing.

LANCE Can nothing speak? He threatens Valentine Master, shall I strike?

PROTEUS Who wouldst thou strike?

LANCE Nothing.

PROTEUS Villain, forbear.

LANCE Why, sir, I'll strike nothing.

(The Two Gentlemen of Verona 3.1.191-204)

This together with the other peculiarities regarding Lance--that he "does not take the letter to Julia referred to in I.i.ii, that he does not accompany Proteus to the court in II.iv (though Speed is in attendance on Valentine there), and that he makes no appearance with his master in the forest--that, indeed, he takes no part at all in the plot" (Shakespeare 1969, 28)--gave Leech to believe that Lance's contributions in scenes 2.3, 2,5 and 4.4 were all late additions and that his contribution to 3.1 was first written for Speed and later transferred to Lance.

Leech's larger theory about stratification in the play's composition has not gained wide acceptance. Indeed, Leech was unable to convince his Arden general editor Harold Brooks to accept it, although Brooks agreed that Lance seems like a late addition (Shakespeare 1969, 31). William C. Carroll found the late insertion of Lance to be the least unconvincing part of Leech's stratification theory (Shakespeare 2004, 126-27) but Roger Warran thought the entire theory to be "based on . . . exaggerated views about the play's contradictions" (Shakespeare 2008, 23n1). Yet there remains something peculiarly slippery about the distinction between Speed and Lance in scene 3.1, which is where Lance is most fully embedded in the action. Lance begins his soliloquy by remarking that he fears Proteus's motives (3.1.260-62) but soon turns to his own love affairs (3.1.263-75), producing and reading a list of his beloved milkmaid's virtues and vices. He gets as far as reading the first two virtues--she can fetch and carry and milk cows--when Speed enters and takes over reading the list. Lance now acts as if he does not know the items in the list he has written and responds, indeed, as if the list were Speed's rather than his own:

SPEED "Item, she is slow in words."

LANCE O villain, that set this down among her vices! To

be slow in words is a woman's only virtue. I pray thee

out with 't, and place it for her chief virtue.

(The Two Gentlemen of Verona 3.1.324-27)

This can be understood as a comedic vacation of the self, a disowning of one's own agency, of the kind that Groucho Marx repeatedly used to considerable effect in jokes such as resigning from a club in protest at their decision to admit someone like himself (Knowles 2009, 526). But more simply, we might suppose that this is one more of the noteable signs that the script has been reworked and its dramatic functions reassigned.

Looking for Stratification using the Zeta Test

We can approach the topic of the alleged stratification of The Two Gentlemen of Verona using the Zeta word-counting test devised by John Burrows and refined and implemented in software by Hugh Craig as the Intelligent Archive (Burrows 2007; Craig & Kinney 2009; Craig & Whipp 2010). The test works by deriving from a pair of electronic texts, called the Base and the Counter, the words whose frequencies of use most distinguish those texts. That is, the test counts the frequencies of all the words present and selects those that are most frequently used in the Base and least frequently used in the Counter (thus, words characteristic of Base) and conversely the words that are least frequently used in the Base and most frequently used in the Counter (thus, words characteristic of the Counter). Once these sets of characteristic marker words are known, their frequencies can be counted in a candidate text to see if it is more like the Base or the Counter in its rates of using them. Typically, the Base and Counter will be texts securely attributed to different authors, the candidate a text of unknown authorship, and the candidate's sharing of word preferences with Base or Counter is presented as evidence for authorship by the same person.

To illustrate the method for investigating whether the alleged stratification of The Two Gentlemen of Verona has a corollary in the play's word choices we can first make an arbitrary division of a text of the play into two halves: the first half (by word-count) we will designate part A and the second part B. These halves contain around 8,000 words each and we may compare one with the other by looking for the top 200 words that each half favours and the other half disfavours.2 If A is distinct from B in its word choices, then any part A should be more like the rest of A in its frequencies of word usages than it is like the whole of B, and any part of B should be more like the rest of B than it is the whole of A. To test this, we divide A into four parts, A1, A2, A3 and A4, comprising the first, second, third and fourth 2,000-word segments of A. Likewise for B divided into B1, B2, B3 and B4. Then we set A1 and B1 aside and use A2+A3+A4 as our Base and B2+B3+B4 as our Counter, from which Zeta produces a set of words that are significantly more common in A2+A3+A4 than they are in B2+B3+B4. These marker words are then counted in A1 and B1 to see if each of these segments is more like A or B generally. If A is generally different from B--as the stratification hypothesis requires--then we would expect A1 to be more like A2+A3+A4 than B1 is like A2+A3+A4. We repeat the process with B2+B3+B4 as our Base and A2+A3+A4 as our Counter, which produces a list of marker words that the B segments favour. Again, If A is generally different from B--the stratification hypothesis--then we would expect A1 to be less like B2+B3+B4 than B1 is like B2+B3+B4.

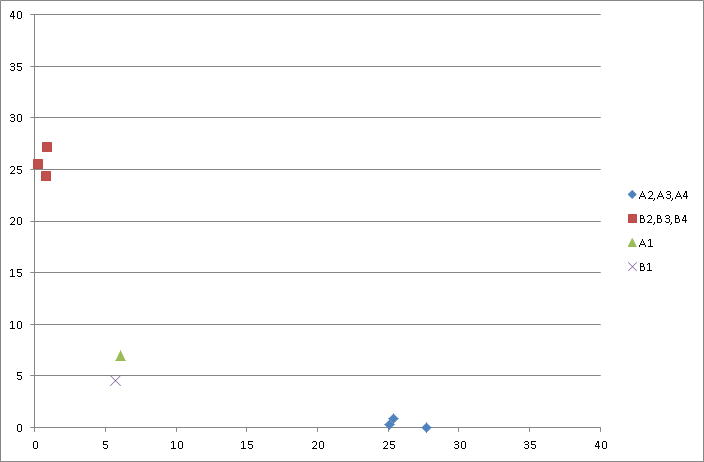

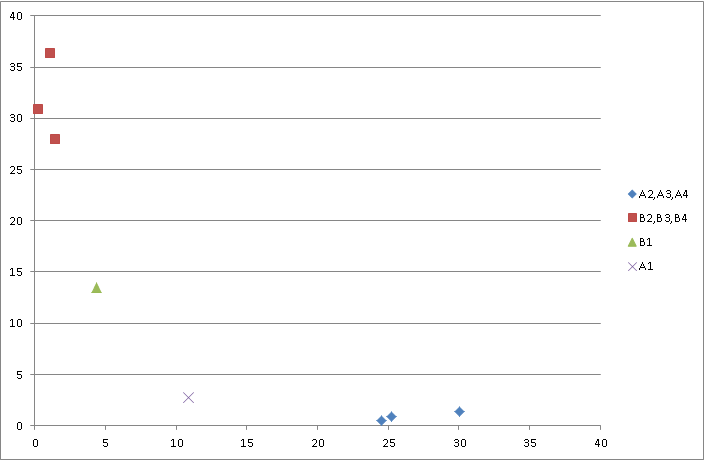

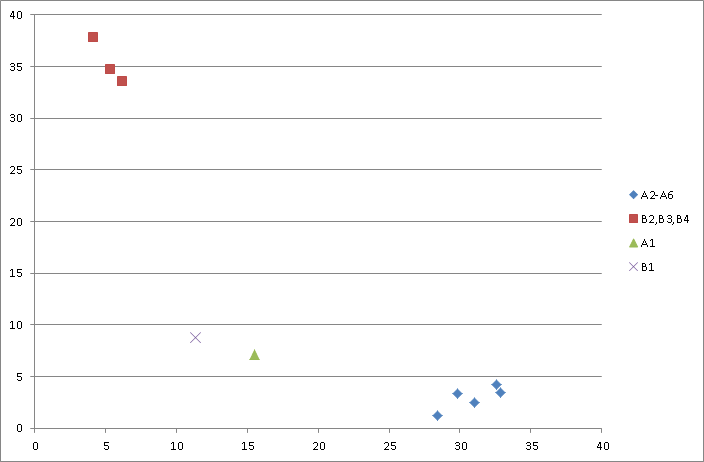

Figure One plots the result for the first of these tests. The x-axis shows each segment's frequency of use of words characteristic of A2+A3+A4 (taken as a group) and the y-axis shows each segment's frequency of use of words characteristic of B2+B3+B4 (taken as a group). The frequencies are calculated by dividing the segment's number of occurrences of the 200 marker words by the number of word types in the segment and multiplying by 100 to give a percentage. Thus in Figure One, around a quarter of the word-types in each of the segments A2, A3 and A4 are words from the list of 200 A-characteristic marker words and almost none are B-characteristic marker words, and likewise around a quarter of the word-types in segments B2, B3 and B4 are words from the list of 200 B-characteristic marker words and almost none are A-characteristic marker words. This clustering in the bottom right and top left corners of the plot is what we would expect because we went looking for precisely the words that would create such clustering, being the words that are distinctive of each half of the play. This does not tell us that the two halves of the play are significantly distinct from one another, since we have deliberately excluded all the words they use equally frequently.

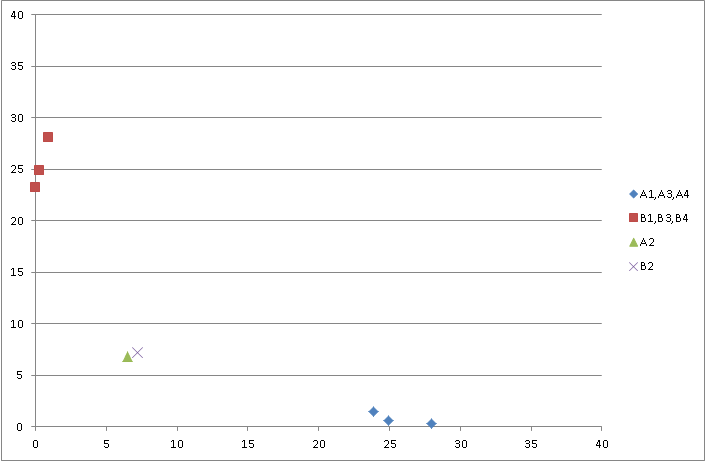

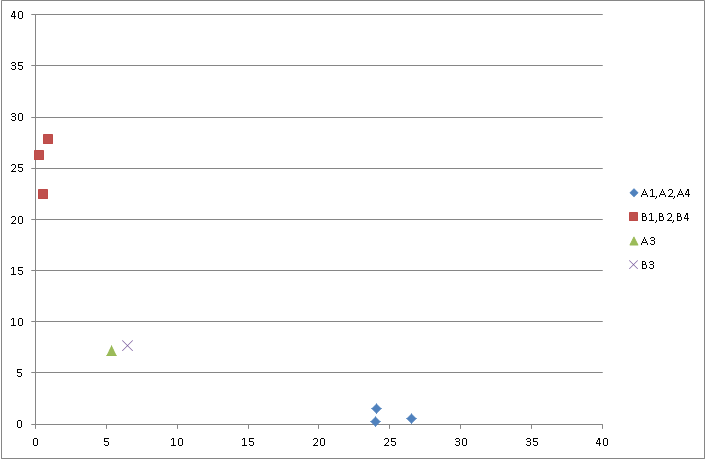

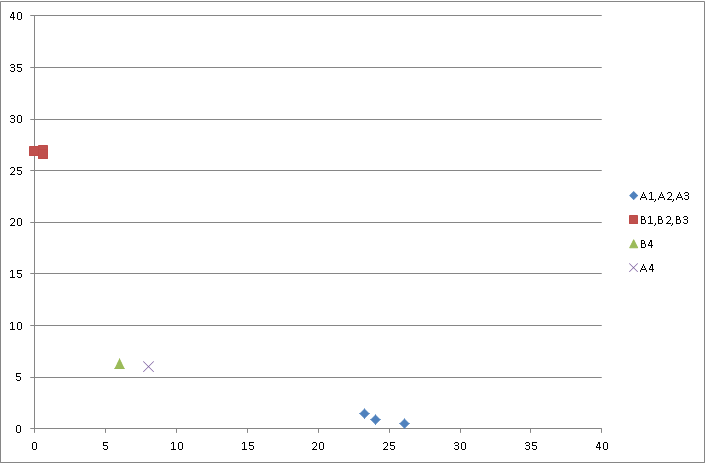

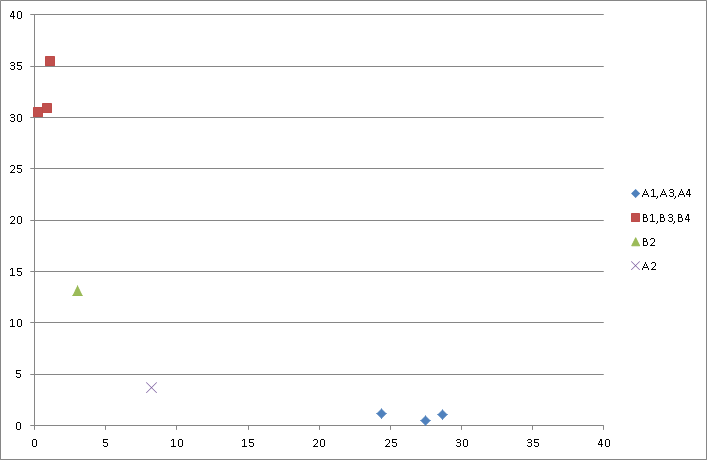

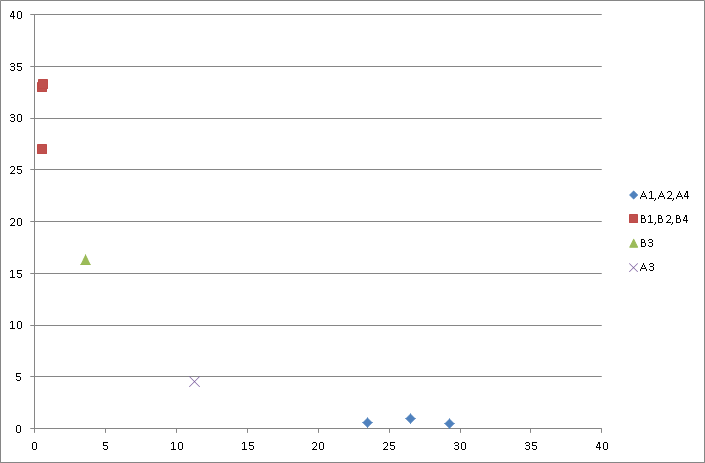

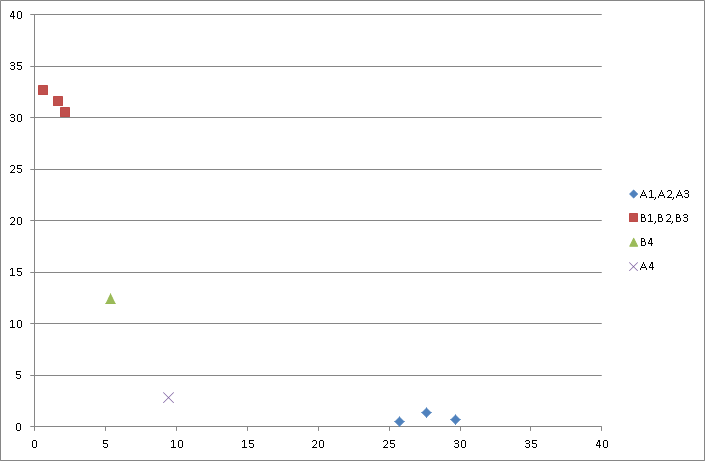

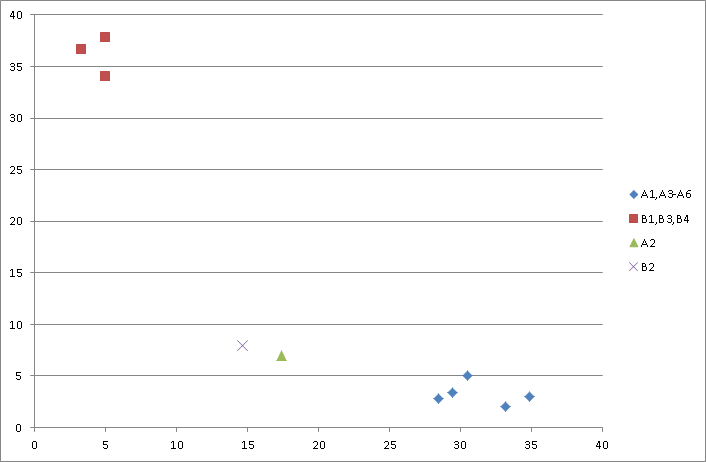

The crucial matter is how frequently the segments A1 and B2 use these words. If the play really divides into two halves, we would expect A1 and B2 to differ in their rates of usage of words characteristic of the half from which they came. That is, A1 should fall nearer to the A2+A3+A4 cluster (because it shares their word preferences) than the B2+B3+B4 cluster, and B1 should fall nearer to the B2+B3+B4 cluster (because it shares their word preferences) than the A2+A3+A4 cluster. This is not what we find: A1 and B1 are roughly equidistant from the two clusters. Figures Two, Three, and Four show that we get the same results when we repeat the tests for A2 and B2 tested against the remainder of their halves (A1+A3+A4 and B1+B3+B4), and so on for A3 and B3 and A4 and B4. That is to say, each eighth of the play in the first half scores like its corresponding eighth in the second half on its frequencies of words characteristic of the rest of the first half, and the same is true for each eighth in the second half.

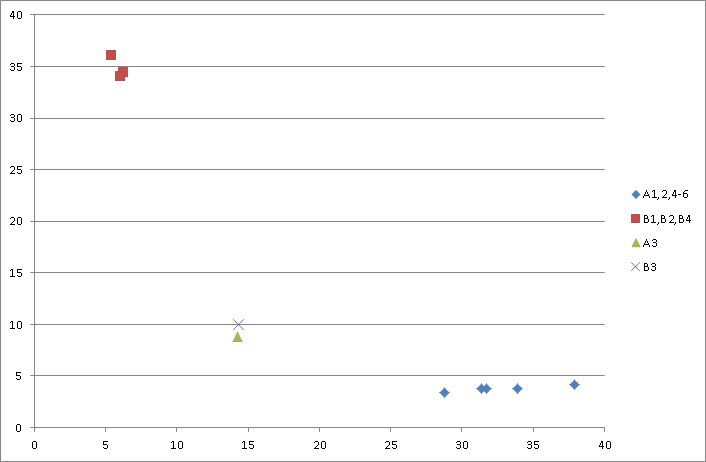

What would we expect these graphs to look like--how far apart would the two tested segments be--if the play really were stratified? To find out, we can run the tests on a fabricated pseudo-text that is genuinely made of disparate halves written by different authors at different times. For this purpose we took as part A the first half of John Lyly's play Sappho and Phao (first performed around 1583) and as part B the second half of John Fletcher's play Rule a Wife and Have a Wife (first performed in 1624). Again A was divided into four quarters, A1 to A4, and B likewise into B1 to B4. Again the search was for the 200 marker words for each half and the software was instructed to treat variant spellings of a word as if they were the same. Figures Five, Six, Seven and Eight show how this intentionally stratified text fared in the Zeta test, and as can be seen the isolated segments A1, A2, A3 and A4 each fell closer to the rest of A than they did B and each of the isolated segments B1, B2, B3 and B4 fell closer to the rest of B than they did A. Without processing the results further, this visualization of the word frequencies confirms that parts A and B constitute distinct strata when considered in terms of their word choices.

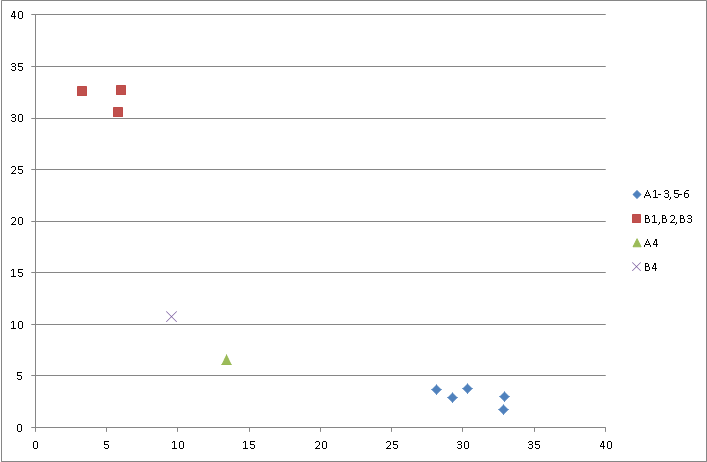

Leech's proposed stratification of The Two Gentlemen of Verona designates the original writing, which we will call part A, as 2.1, 2.4, 3.1.1-259, 3.2, 4.1, 4.2, 4.3, 4.4.60-202, 5.1, 5.2, 5.3 and 5.4, totalling 10,556 words, and the later writing, our part B, as 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 2.2, 2.3, 2.5, 2.6, 2.7, 3.1.260-372 and 4.4.1-59, totalling 6,499 words. (Line references here are keyed to Shakespeare 1989; textual and line-referencing variations between editions are for this play negligible.) Rather than using 2,000-word segments, these strata suggest use of 1,625-word segments, with part A having six such segments, A1-A6 (and we throw away the last 806 words), and part B having four such segments, B1-B4, the last of which is one word short. We could eliminate the differences in the size of A and B by discarding segments A5 and A6 altogether, but in fact there is no harm in allowing these to contribute to the lists of marker words that distinguish parts A and B. We will in any case test only how A1-A4 compare to B1-B4, to preserve parity with the preceding tests that established our expections regarding segments' clustering in the event of a play truly being made of disparate strata.

Figures Nine, Ten, Eleven and Twelve show how the segment pairs A1-B1, A2-B2, A3-B3 and A4-B4 fall on graphs that show on the x-axis each segment's count of marker words favoured by part A and on the y-axis each segment's count of marker words favoured by part B. As before, and as expected, segments from part A score highly on A-favoured words (high x) and lowly on B-favoured words (low y) and segments from part B score lowly on A-favoured words (low x) and highly on B-favoured words (high y). The scores of the segment pairs A1-B1 and A4-B4 are noticeably unlike those arising when we arbitrarily divided our play into first-half and second-half strata (Figures One, Two, Three and Four) and similar to the scores achieved when we created a strongly stratified pseudo-text made of the front half of Lyly's Sappho and Phao and the back half of Fletcher's Rule a Wife and Have a Wife (Figures Five, Six, Seven and Eight). For these pairs, the segments are, as it were, 'attracted' towards their home strata. On this evidence, there appear to be grounds for supposing that Leech's proposed stratification of the play does indeed reflect differences in word preferences in different parts of the play.

Leech's proposed stratification represented Shakespeare's solo reworking of his own materials over a period of up to two years, which process we would not expect to produce a strong distinction in the word choices in the two strata. The results we see from testing Leech's proposed stratification, however, are distinctly similar to, although less extreme than, those found in the stratification of an authorially hybrid play. It is worth reviewing the current state of our knowledge about the earliest printed editions of Shakespeare's plays and what we know about their composition:

Arden of Faversham (printed 1592)

Titus Andronicus (printed 1594)

The Contention of York and Lancaster / 2 Henry 6 (printed 1594)

Richard Duke of York / 3 Henry 6 (printed 1595)

Edward 3 (printed 1596)

I have omitted from this list the reprints of existing editions: these are just the first editions. I take as accepted the recent arguments for Shakespeare contributing to Arden of Faversham and Edward 3 and that he collaborated with others, quite possibly including Christopher Marlowe, on his first two plays about King Henry 6, and that George Peele wrote the first act of Titus Andronicus (Craig & Kinney 2009; Craig & Burrows 2012). A key fact to observe, then, is that every one of these early plays was a collaborative effort by Shakespeare. On this evidence, early Shakespearian drama is collaborative drama. On the evidence presented here, perhaps The Two Gentlemen of Verona is also a collaborative play.

Figures

Figure One The Two Gentlemen of Verona divided into first (A) and second (B) half, each half divided into four 2,000-word segments. The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A2+A3+A4 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B2+B3+B4.

Figure Two The Two Gentlemen of Verona divided into first (A) and second (B) half, each half divided into four 2,000-word segments. The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A1+A3+A4 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B1+B3+B4.

Figure Three The Two Gentlemen of Verona divided into first (A) and second (B) half, each half divided into four 2,000-word segments. The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A1+A2+A4 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B1+B2+B4.

Figure Four The Two Gentlemen of Verona divided into first (A) and second (B) half, each half divided into four 2,000-word segments. The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A1+A2+A3 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B1+B2+B3.

Figure Five The first half of Sapho and Phao (part A) and the second half of Rule a Wife and Have a Wife (part B), each part divided into four 2,000-word segments. The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A2+A3+A4 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B2+B3+B4.

Figure Six The first half of Sapho and Phao (part A) and the second half of Rule a Wife and Have a Wife (part B), each part divided into four 2,000-word segments. The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A1+A3+A4 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B1+B3+B4.

Figure Seven The first half of Sapho and Phao (part A) and the second half of Rule a Wife and Have a Wife (part B), each part divided into four 2,000-word segments. The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A1+A2+A4 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B1+B2+B4.

Figure Eight The first half of Sapho and Phao (part A) and the second half of Rule a Wife and Have a Wife (part B), each part divided into four 2,000-word segments. The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A1+A2+A3 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B1+B2+B3.

Figure Nine The Two Gentlemen of Verona divided into Leech's proposed first stratum (part A) and second stratum (part B), each part divided into 1,625-word segments (6 segments for part A, 4 segments for part B). The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A2+A3+A4+A5+A6 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B2+B3+B4.

Figure Ten The Two Gentlemen of Verona divided into Leech's proposed first stratum (part A) and second stratum (part B), each part divided into 1,625-word segments (6 segments for part A, 4 segments for part B). The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A1+A3+A4+A5+A6 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B1+B3+B4.

Figure Eleven The Two Gentlemen of Verona divided into Leech's proposed first stratum (part A) and second stratum (part B), each part divided into 1,625-word segments (6 segments for part A, 4 segments for part B). The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A1+A2+A4+A5+A6 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B1+B2+B4.

Figure Twelve The Two Gentlemen of Verona divided into Leech's proposed first stratum (part A) and second stratum (part B), each part divided into 1,625-word segments (6 segments for part A, 4 segments for part B). The x-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set A1+A2+A3+A5+A6 and the y-axis shows each segment's percentage of word types shared with the list of 200 marker words favoured by the set B1+B2+B3.

Notes

1All quotations from, and references to, the play are from Shakespeare 1989.

2Stratification created by authorial revision of parts of a play is unlikely to produce significant differences in the spellings of particular words because most writer's spelling habits change relatively slowly, and the subsequent imposition of scribal and compositorial spelling preferences are in this case likely to swamp any such authorial drift. Thus for our purposes all spellings of one word should count equally as a use of that word. The Intelligent Archive software is able to normalize spellings where (as in this case) the input text explicitly lemmatizes such variations and additionally to apply its own rules of normalization arising from substantial research on algorithmic methods for doing so (Craig & Whipp 2010). The text used here was an XML-encoded transcription of the 1623 Folio edition conforming to the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) schema, supplied with the Intelligent Archive software provided by its author Hugh Craig. The Intelligent Archive's normalization of spelling was switched on for these experiments.

Works Cited

Burrows, John. 2007. "All the Way Through: Testing for Authorship in Different Frequency Strata." Literary and Linguistic Computing 22. 27-47.

Craig, Hugh and Arthur F. Kinney. 2009. Shakespeare, Computers, and the Mystery of Authorship. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press.

Craig, Hugh and John Burrows. 2012. "A Collaboration About a Collaboration: The Authorship of King Henry VI, Part Three." Collaborative Research in the Digital Humanities: A Volume in Honour of Harold Short, on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday and His Retirement, September 2010. Edited by Marilyn Deegan and Willard McCarty. Farnham. Ashgate. 27-65.

Craig, Hugh and R. Whipp. 2010. "Old Spellings, New Methods: Automated Procedures for Indeterminate Linguistic Data." Literary and Linguistic Computing 25. 37-52.

Knowles, Elizabeth. 2009. Oxford Dictionary of Quotations. Seventh edition. Oxford. Oxford University Press.

Shakespeare, William. 1623. Comedies, Histories and Tragedies. STC 22273 (F1). London. Isaac and William Jaggard for Edward Blount, John Smethwick, Isaac Jaggard and William Aspley.

Shakespeare, William. 1921. The Two Gentlemen of Verona. Ed. Arthur Quiller-Couch and John Dover Wilson. The New Shakespeare. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press.

Shakespeare, William. 1969. The Two Gentlemen of Verona. Ed. Clifford Leech. The Arden Shakespeare. London. Methuen.

Shakespeare, William. 1989. The Complete Works. Ed. Stanley Wells, Gary Taylor, John Jowett, and William Montgomery. Electronic edition prepared by William Montgomery and Lou Burnard. Oxford. Oxford University Press.

Shakespeare, William. 2004. Two Gentlemen of Verona. Ed. William C. Carroll. The Arden Shakespeare. London. Thomson Learning.

Shakespeare, William. 2008. The Two Gentlemen of Verona. Ed. Roger Warren. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford. Oxford University Press.