"Babbling of green fields: Shakespearian ecocriticism in theory" by Gabriel Egan

Introduction

My title is taken from the Hostess's description of Falstaff's death in Henry 5 (2.3.16-171) in which the fat knight, in his dying delirium, apparently remembers his and England's verdant youthhood. Babbling about greenery is something Shakespearian ecocriticism should avoid. In this short paper I explain one of the senses in which a claim commonly thought to be spiritualist in some form or another--the claim that the Earth, as a whole, is alive--is scientifically true. This paper is part of a larger project, a book on Shakespeare and ecocriticism, that will revaluate Elizabethan and Jacobean conceptions about the relationship between humankind and the natural world, particularly as expressed in the drama, in order to suggest a critical agenda that leads from current dissentient politics (which are currently closely allied with forms of spiritualism) towards a rational, Marxist ecocriticism. As the essential matters of science on which ecocriticism may be founded are not well known by Shakespearians, I will take some time to outline one of them, the Gaia hypothesis, and crave the reader's indulgence with the promise that we will get to Shakespeare eventually.

The Gaia Hypothesis and DaisyWorld

You probably won't have noticed, but the sun has been getting hotter. If you were 3.6 billion years old--that is to say, if you were born when life started on Earth--the sun's output of energy would have increased by about 30% over your lifespan, yet the Earth's surface has remained between 10 and 20 degree Celsius all this time. To understand why requires the Gaia hypothesis first formerly presented by James E. Lovelock (1972) and subsequently expanded upon by Lovelock and Lynn Margulis (1974a; 1974b). The Greek word ca´a (Gaia) or cž (Ge) meant 'Earth', hence our English prefix geo- for earth-related nouns, and was suggested to Lovelock by William Golding when he heard Lovelock's ideas in 1967. The essence of the Gaia hypothesis is that the Earth is a single organism comprised of the obviously alive biota (all the lifeforms we recognize) and the parts we have previously treated as inorganic, the 'background' environment such as the rocks, oceans, and atmosphere. It doubtless seems odd to include the inanimate rocks in any organism, but it is worth remembering that most of a tree is in fact dead material accreted over its lifetime and stored away in the trunk: only the bark actually 'lives' by the organic processes we recognize. To understand why this is a reasonable scientific (and hence materialist) way think about Earth, Lovelock invented a simple model of a Gaia process and called it DaisyWorld (Lovelock 1983).

DaisyWorld is a spherical planet uniformly bathed in light from a sun, upon which there happens to be seeds for two kinds of plant: white daisies and black daisies. White daisies reflect a lot of light and hence keep themselves and their surroundings cool, but they don't photosynthesize as efficiently as black daisies, which absorb a lot of light and quickly warm themselves and their surroundings. Both kinds of daisy thrive at the same ideal temperature, but to begin with their sun isn't producing enough energy for either to germinate. As suns across the universe do, theirs heats up and as the surface temperature rises both plants begin to grow and populate Daisyworld. In this initially cold climate, the black daisies do rather better than the white ones because they are better at photosynthesis and for a while most of the planet is covered with black daisies because of natural selection. A mostly-black DaisyWorld reflects little light and the entire planet warms up rather more quickly that it would have were it barren. As the sun's output continues to rise the relative advantage of the black daisies diminishes: there's so much light that even white daisies have enough to photosynthesize efficiently and they begin to return. This is just as well because the ever-rising output of the sun is making DaisyWorld rather too hot for daisies, but of course the white, reflective daisies are less affected by this than the black, absorptive daisies are. As the temperature rises still further the black daisies die off and the white daisies come to dominate the planet's surface, and a mostly-white DaisyWorld reflects much of the sun's energy, keeping things cool enough for life to go on. Eventually, of course, the sun's energy is so great that not even a white daisy-cooled planet can sustain life and eventually all the daisies die.

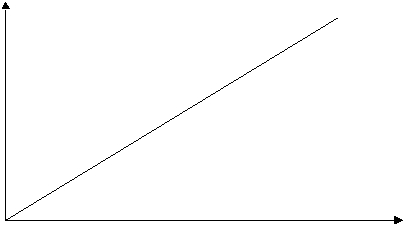

The significant thing about this scenario is that in a model where the sun got increasingly hot, the temperature on DaisyWorld remained roughly the same (near the ideal for daisies) while it supported life, because the ratio of black to white daisies shifted precisely as needed to counteract the effect of overheating. The daisies did this without any planning or design, it was merely that the eco-system in general (comprised of the organic matter, the daisies, and the inorganic matter, the surface of DaisyWorld that they grow on) formed what is called a negative-feedback loop, regulating the planet's surface temperature. At the extremes this regulation did not work: when it was too cold at the beginning and too hot at the end, no daisies survived. But for a significant time between these extremes, the energy from their sun rose steadily yet the surface temperature of DaisyWorld remained stable. To visualize what happened, here's a plot of the sun's heat output:

(x-axis is Time, y-axis is Temperature on DaisyWorld)

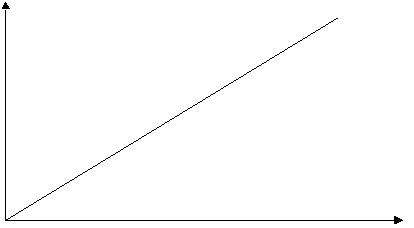

If DaisyWorld were lifeless, as most planets are, its temperature would simply rise with the sun's increasing output:

(x-axis is Time, y-axis is Temperature on DaisyWorld)

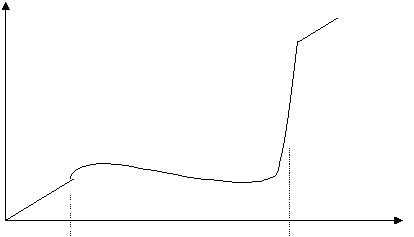

With daisies growing on DaisyWorld, however, something remarkable happens:

(x-axis is Time, y-axis is Temperature on DaisyWorld)

There's a roughly level area between the time (marked by the first dashed vertical line) when DaisyWorld became warm enough to support daisies, and the time (marked by the second dashed line) when the sun's output became just so great that even when entirely covered in white, reflective daisies DaisyWorld became just too hot and no daisies could survive. If the sun's output were only to vary within the boundaries of this plateau (imagine the time-line dashes being marked on the first plot), the temperature on DaisyWorld would remain roughly constant. Within that plateau, one might say that DaisyWorld is regulating its own temperature by adjusting the ratio of black to white daisies to keep things just right for life to be supported.

You will accuse me of anthropomorphizing: DaisyWorld is not really 'alive' and so cannot regulate its own temperature in the way that biota do. This was the common view of biologists when Lovelock first proposed his Gaia hypothesis, but in the last twenty years great changes in the philosophy of science have convinced many people that the traditional distinction between 'alive' and 'dead' and between 'individual' and 'others' can be as misleading as the distinction between 'nature' and 'culture'. This can best be exampled in genetics. There is a parasitic fluke (flatworm) that lives inside a certain species of snail and interferes with the snail's hormonal system to increase the signal controlling how thick a shell the snail will grow. The snail ends up with a thicker shell than it really needs and this wasted energy lowers the infected snail's ability to reproduce. This is of no concern to the fluke, whose 'investment' is in the particular snail it has infested, not its descendents. So long as this particular snail doesn't get killed (and for this a thick shell helps) the fluke can reproduce. Zoologists have traditionally thought of the limit of the effect of an organism's genotype (collection of genes) to be its phenotype (body), but in this case one can truly say that the fluke carries the gene for 'thick shells' even though the fluke hasn't got a shell and only borrows the one of its host (Dawkins 1989, 240-42). Certainly, a fluke that doesn't carry the gene for thickening its host's shell will lose out in the competition for survival with those that do, and so the 'thick shell' gene will be naturally selected. Looked at another way, one might say that since a spider's web is as much an effect of its genes as its hairy legs--the web-making behaviour is innate not learned--the distinction between the traditional phenotype (the hairy body) and the product made by that phenotype (its web) is false. Richard Dawkins, who pointed out this error, suggested that we should take into account all the effects of genes and think about The Extended Phenotype, (1982), as he called his book.

Elizabethan Ideas about the Universe: The case of blackness

Like a number of recent scientific developments such as memetics and artificial intelligence, Lovelock's Gaia hypothesis has disturbing implications for modern critical theory, threatening to disrupt the distinctions by which we work, such as nature/culture and lifeform/environment. Shakespearians are particularly well-placed to deal with these disruptions because we work on texts from a relatively unfamiliar culture that, while it probably did not treat as indisputably true the cosmlogical model described in E. M. W. Tillyard's The Elizabethan World Picture (1943), clearly contained many views about the universe that we consider mistaken. Their sense of a connection between the affairs of human beings in the sublunary sphere and occurrences among the higher layers (the sky, planetary spheres, and the fiery realm) was firmly, and it seemed at the time irrevocably, ruptured in the eighteenth-century Enlightenment. We might argue about the extent to which this connection was generally believed in the Renaissance, and can blame Tillyard for promulgating a naive view of ideological cohesiveness that gave too little space to reasoned dissent from the dominant beliefs of the period. But characters in Shakespeare speak meaningfully about comets presaging disaster and the music of the spheres, and unless we think that these lines always elicited derisive laughter from the theatre audiences we have to accept that such things were within the realm of the believable. And they now are not. Or are they? One of the most noticeable cultural developments in the Western world in the past 30 years has been the rise of an anti-rationalistic, 'alternative' culture that embraces the New Age movement, complementary medicine, and forms of holistic spiritualism, and links these to broader anarchist and animal rights movements. One public example is the artistic director of Shakespeare's Globe in south London, where I work, who publicly proclaims his belief in the power of pyramidic shapes to preserve fruit and has chosen touring sites for his own company, Phoebus Cart, by searching on a map for the intersections of leylines. For an apparently rising number of people the Enlightenment itself was an illusory detour into hyper-rationality and the sense of connectedness voiced in Elizabethan drama and poetry offers a form of non-religious spirituality that comes packaged with a rich supply of artistic works that are already central to Western culture. My view that we should reject such uses of Shakespeare I would like to illustrate by his characters' understanding of why black people are that colour.

The black daisies of DaisyWorld retain heat energy that strikes them while the white ones reflect it away. Anyone who has changed from black to white clothes or vice versa on a sunny day will have noticed that black materials retain heat energy. The prevailing Renaissance conception of how black people come to be black is clearly expressed by characters in Shakespeare. In The Merchant of Venice the prince of Morocco anticipates (correctly, as it turns out) that Portia is racist:

MOROCCO (to Portia) Mislike me not for my complexion,

The shadowed livery of the burnished sun,

To whom I am a neighbour and near bred.

(The Merchant of Venice 2.1.1-3)

His blood, he goes on to insist, is as red as anyone else's, but the important point for my purpose is his idea that his blackness is a coating ("shadowed livery") caused by living in a sunny country. Desdemona's father uses the same idea of burnt coating that should so revolt his daughter that only Othello's use of magic could have caused her to "Run from her guardage to the sooty bosom / Of such a thing as thou" (Othello 1.2.71-2). Othello shares (or perhaps comes to share) this sense of his blackness as a coating: convinced that Desdemona is unfaithful he says "My name, that was as fresh / As Dian's visage, is now begrimed and black / As mine own face. (3.3.391-3). In the very act of denying that blackness can wash off, Aaron in Titus Andronicus imagines it not as an innate colour but a coating:

Coal-black is better than another hue

In that it scorns to bear another hue;

For all the water in the ocean

Can never turn the swan's black legs to white,

Although she lave them hourly in the flood.

(Titus Andronicus 4.2.98-102)

Washing the Ethiop (or blackamore) white was, of course, proverbial in Shakespeare's time (Dent 1981, Appendix A, E186), and I am interested in the conception of the world that gives rise to the idea that blackness is a coating. For a white actor playing Morocco, Othello, or Aaron the character's sense of his blackness as a coating is, of course, literally true: excluding the unlikely possibility that a black actor worked in Shakespeare's company (about which we would expect there to be some record), the actor would have 'blacked up' with a coating as preparation for the performance. The part, then, with its references to blackness as a coating, is inherently suited to a white actor in makeup and not a black actor at all, and this adds support to the argument made by Ghanaian actor Hugh Quarshie that black people should not play Othello at all, or at least not without major reworking of the play (Quarshie 1999).

An observation of the distribution of skin colours around the world would have indicated to Elizabethans that black people live in hot countries, and many things (including white skin) do darken under strong sunlight, so a reasonable assumption would have been that black people simply had really good tans. And in a sense they do: the melanin pigment causing brownness is the same in all humans. But in this humans and DaisyWorld daisies are fundamentally unalike, for we tan in the sun not in order to absorb more of the sun's energy but as a protection from it. The heat energy of the sun would not do us much harm, but its ultraviolet light promotes errors in the copying of genetic material during cell division and can produce in us clusters of out-of-control skin cells, cancers. In countries where sunshine is strongest, humans whose melanocyte cells are especially active, producing greater amounts of the skin pigment melanin, are less likely to get skin cancers because this brown pigment absorbs ultraviolet light before it penetrates too far into the body. Such people have a competitive advantage over those with less active melanocyte cells and so over time dark skins were naturally selected, although once human populations spread around the world the advantage became less pronounced. Those living in cold northerly climates would in fact be at a relative disadvantage if they made excessive melanin--making it costs energy that were better spent elsewhere in the body--and hence they turned more fair.

Importantly, the operations giving rise to colour differences between the races operate by Darwinian selection across a population, not on an individual, but nonetheless it is true to say that the hot sun makes black people black. It is equally true to say that the sun shining on DaisyWorld made it turn white, and so the empirical observation can be literally true even within an utterly deficient model of how the processes operate. There is an instructive analogy here between the scientific view and the thinking of poststructuralists for whom binary oppositions of the kind black/white are false, human distinctions in which the supposedly opposing terms actually have much in common. The word 'black' comes from the Old Teutonic word 'blækan' meaning to scorch and the word 'bleach' has the same origin, because an object placed in a fire turns first black and then, after a while, white. So 'bleaching' (making white) and 'blackening', far from being natural opposites, are cognate. Our binary opposition, like so many false oppositions, has just deconstructed itself. However, where the poststructuralist view depends ultimately only on linguistics (and hence ancient experience), the apparently opposing scientific explanations (sun > black skin, sun > white DaisyWorld) are both entirely scientific.

Conclusion: Which kinds of spirituality are ecocritical?

Ecocriticism as it is currently constituted has an essentially conservative political ambition: that humankind cease harming the ecosphere. In a much-quoted definition, one of the field's founders, Cheryll Glotfelty, made an analogy with two political schools of criticism and offered examples of what the criticism might do:

Simply put, ecocriticism is the study of the relationship between literature and the physical environment. Just as feminist criticism examines language and literature from a gender-conscious perspective, and Marxist criticism brings an awareness of modes of production and economic class to its reading of texts, ecocriticism takes an earth-centered approach to literary studies.

Ecocritics and theorists ask questions like the following: How is nature represented in this sonnet? What role does the physical setting play in the plot of this novel? Are the values expressed in this play consistent with ecological wisdom? How do our metaphors of the land influence the way we treat it? How can we characterize nature writing as a genre? In addition to race, class, and gender, should place become a new critical category? . . .

Despite the broad scope of inquiry and disparate levels of sophistication, all ecological criticism shares the fundamental premise that human culture is connected to the physical world, affecting it and affected by it. (Glotfelty 1996, xviii-xix)

This is at once a vague statement of principles--who could disagree with the premise that "human culture is connected to the physical world"?--and a specific set of enquiries (there were 8 more I have elided). Obvious theoretical objections are immediately apparent, for example that 'place' should not be a new critical category alongside race, class, and gender because i) it is hopelessly imprecise (was this poem written upstairs or in the basement?), and ii) race, class, and gender should not form a critical triplet in the first place.

The second of these two errors has a respectable Shakespearian history, for example in Jonathan Dollimore and Alan Sinfield's introduction to their anthology Political Shakespeare, which proclaimed that their new approach "registers its commitment to the transformation of a social order which exploits people on grounds of race, gender, and class" (Dollimore & Sinfield 1985, viii). The problem, of course, is the patently absurd idea that capitalist society exploits on the grounds of class, here likened to the categories of race and gender. One can see where a social-constructionist view of history might lead: race, gender, and class are categories (defined by material difference) created by the prevailing social order, which then exploits people for belonging to the wrong one(s). Where Marx would disagree is about the category class, which he thought merely a convenient generalization about people's relations to production, and the most important category simply because capitalism will necessarily cast greater numbers of people into one class, the proletariat, until that class is large enough to overthrow the bourgeoisie. Nobody wants to be poor, of course, but it is far from clear that everyone wants to be released from the categories of race and gender; if only being a woman did not entail doing more housework and earning less money than men, it would not of itself seem a condition of oppression. Likewise, those in Britain's first overseas colony have long struggled to be free, but have tended to consider their oppression in terms of the economic wealth extracted from their island rather than in the condition of simply being Irish. By likening race, gender, and class, Dollimore and Sinfield abandoned the Marxist insight that class is a unique category, not an incidental attribute by which one might be oppressed, and without this the political project diminishes to liberal reformism that treats the social order as a given and hopes only for a meritocracy in which being from the wrong race, gender, or class would be no barrier to advancement.

Dollimore and Sinfield's slip was uncharacteristic of their work and that which their anthology presented, but Glotfelty's avoidance of materialism is of a piece with essays in her anthology. These are suffused with a variety of anti-intellectual spiritualisms of which Paul Gunn Allen's is amongst the most invidious: "The westerner's bias against nonordinary states of consciousness [produced in American Indian ceremonies] is the result of an intellectual climate that has been carefully fostered in the west for centuries, that has reached its culmination in Freudian and Darwinian theories, and that only now is beginning to yield to the masses of data that contradict it" (Allen 1996, 255). And even those of us who marvel at the self-regulatory processes of DaisyWorld might well feel that William Rueckert is unlikely to win over the opponents of ecocriticism with such claims as "Green plants, for example, are among the most creative organisms on earth. They are nature's poets. . . . Poems are green plants among us; if poets are suns, then poems are green plants among us for they clearly arrest energy on its path to entropy . . ." (Rueckert 1996, 111 repetition as in original). Ecocriticism seems to occupy a critical position something like that held by feminism 30 years ago, when ideas of breath-taking idiocy such as Shulamith Firestone's projects for reproductive liberation via artificial placentas and limited contract households (Firestone 1970, 197-8l, 231) jostled for space alongside (indeed, in Firestone's case, within the same covers as) serious political scholarship.

Materialism, the view that the basic substance of the world is matter and that it is known primarily through and as material forms and processes, is not the opposite of spiritualism. Materialism finds its opposite in metaphysical idealism (which asserts the ideality of reality) and in epistemology the contrast is between realism (which holds that in human knowledge objects are grasped and seen as they really are, independent of the human mind) and epistemological idealism (which holds that in the knowledge process the mind can grasp only the psychic or that its objects are conditioned by their perceptibility). Spiritualism is something altogether distinct, but, like essentialism, literary theorists frequently drew it in to form a simple, mistaken dualism that is homologous to head/heart. By such distorted categorizing one is either headily materialist and realist or one is heartily spiritualist, idealist, and essentialist. In fact, it is entirely possible to hold onto opinions that have long been deemed spiritualist (such as the view that the Earth itself, rocks, sea water, and all, is singly alive) while insisting upon materialist explanations. For most of us there has to be a materialist explanation of human consciousness, and yet we are quite content to exalt in the undiminished 'spirit', as we call it, of Venezualans who restored their elected leader Hugo Chavez to presidential office in the teeth of a CIA-backed insurgents in late 2002. Consciousness can be explained at a number of different levels, including that of post-Cold War international politics and the rise of American aggression around the world, and at a global level in relation to the self-regulation of Earth's ecosystem. That we possess the conceptual facility necessary to reject Kyoto-busting American capitalism and intelligently to subvert its locally and globally harmful effects is one of the marvels of human nature. This marvel of consciousness is to no extent diminished by thinking of it, as Daniell C. Dennett does, as the Earth growing its own nervous system (Dennett 2003, 4)

Notes

1All quotations of Shakespeare are from Shakespeare 1989.

Works Cited

Allen, Paula Gunn. 1996. "The Sacred Hoop: A Contemporary Perspective." The Ecocriticism Reader: Landmarks in Literary Ecology. Edited by Cheryll Glotfelty and Harold Fromm. Athens GA. University of Georgia Press. 241-63.

Dawkins, Richard. 1982. The Extended Phenotype: The Gene as the Unit of Selection. Oxford. Oxford University Press.

Dawkins, Richard. 1989. The Selfish Gene. Second edition. Oxford. Oxford University Press.

Dennett, Daniel C. 2003. Freedom Evolves. London. Penguin.

Dent, R. W. 1981. Shakespeare's Proverbial Language: An Index. Berkeley. University of California Press.

Dollimore, Jonathan and Alan Sinfield. 1985. "Foreword: Cultural Materialism." Political Shakespeare: New Essays in Cultural Materialism. Edited by Jonathan Dollimore and Alan Sinfield. Manchester. Manchester University Press. vii-viii.

Firestone, Shulamith. 1970. The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution. New York. Morrow.

Glotfelty, Cheryll. 1996. "Introduction: Literary Studies in an Age of Environmental Crisis." The Ecocriticism Reader: Landmarks in Literary Ecology. Edited by Cheryll Glotfelty and Harold Fromm. Athens GA. University of Georgia Press. xv-xxxvii.

Lovelock, James E. 1972. "Gaia as Seen Through the Atmosphere." Atmospheric Environment. 6. 579-80.

Lovelock, James E. 1983. "Daisy World: A Cybernetic Proof of the Gaia Hypothesis." Coevolution Quarterly. 38. 66-72.

Lovelock, James E. and Lynn Margulis. 1974a. "Atmospheric Homeostasis By and for the Biosphere: The Gaia Hypothesis." Tellus. 26. 2-9.

Lovelock, James E. and Lynn Margulis. 1974b. "Biological Modulation of the Earth's Atmosphere." Icarus. 21. 471-89.

Quarshie, Hugh. 1999. Second Thoughts About Othello. International Shakespeare Association Occasional Papers. 7. Chipping Campden. International Shakespeare Association.

Rueckert, William. 1996. "Literature and Ecology: An Experiment in Ecocriticism." The Ecocriticism Reader: Landmarks in Literary Ecology. Edited by Cheryll Glotfelty and Harold Fromm. Athens GA. University of Georgia Press. 105-23.

Shakespeare, William. 1989. The Complete Works. Ed. Stanley Wells, Gary Taylor, John Jowett, and William Montgomery. Electronic edition prepared by William Montgomery and Lou Burnard. Oxford. Oxford University Press.

Tillyard, E. M. W. 1943. The Elizabethan World Picture. London. Chatto and Windus.