teaching

Here will appear miscellaneous documents that relate to my teaching and research-student supervision.

Referencing for dummies

If you've not learnt a referencing system already, the easiest to start with is the author-date system, which uses no footnotes or endnotes at all. Recall that every assertion you make in a essay (apart from things that are Common Knowledge) has to be substantiated with a reference to an authority. Thus the following sentence in an essay needs a reference:

The parliament closed the theatres in 1642.

Your assertion might involve quotation of someone, in which case you undoubtedly need a reference:

Kastan showed that it is a mistake to think that "ever-growing Puritan hostility to the theater resulted in the prohibition of playing".

In the author-date system, your reference consists of an author's last name and the year of publication of the work and, if a particular page is being referenced, the page number. Thus the first sentence (the authority for which is a whole chapter in Kastan's book) would be cited thus:

The parliament closed the theatres in 1642 (Kastan 1999, 201-20).

The second sentence, which quotes from a particular page, would be supported thus:

Kastan showed that it is a mistake to think that "ever-growing Puritan hostility to the theater resulted in the prohibition of playing" (Kastan 1999, 203).

These in-text citations refer the reader to a single list of 'Works Cited' (much like a bibliography) at the end of your essay, in which the combination of author and date identifies a single work. A 3-item list of works cited might look like this:

Works Cited

Gurr, Andrew The Shakespearian Stage (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999)

Harbage, Alfred Shakespeare's Audience (New York: Columbia University Press, 1941)

Kastan, David Scott Shakespeare After Theory (New York: Routledge, 1999)

What matters most is that you name the author, title, city of publication (NOT the country or county), the publisher, and the year. If you have all these things, no-one's going to mind too much how you style them (whether separated by commas, periods, brackets, etc). There's no need to reproduce the words 'Ltd' or '& Co' or 'PLC' in a publisher's name, just the name will do. The title of the book must be italicized or underlined.

The in-text citation of author and date is sufficient to identify the unique work in the list of works cited, even if a single author has multiple works in there (since the year will disambiguate them). If, by chance, there are two works by the same author in the same year, you disambiguate them by adding 'a', 'b', 'c', etc to the year thus:

The parliament closed the theatres in 1642 (Kastan 1999a, 201-20). But play publishing continued (Kastan 1999b, 22).

In the list of works cited, the items would appear as:

Works Cited

Kastan, David Scott Shakespeare After Theory (New York: Routledge, 1999a)

Kastan, David Scott Yet Another Book by Me (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999b)

If a book has two authors, both names appear in the in-text citation, thus "(Kastan & Wells 2003, 21)"

What if the item is an article in a journal? The same rules apply to the in-text citation--eg "(Gurr 1988, 58)"--but in the list of works cited you give slightly different information: the author, the title of the article (in inverted commas), the name of the journal it appeared in (in italics or underlined), the volume of the journal it appeared in (that is, a volume number), the year of publication, and the span of pages that the article occupies. Thus:

Gurr, Andrew "The bare island" Shakespeare Quarterly 44 (1988) 55-70

What if the item is an essay in a collection of essays forming a book? The same rules apply to the in-text citation--eg "(Holderness 1990, 20)"--but in the list of works cited you give slightly different information: the author, the title of the article (in inverted commas), the title of the book of essays, the name of the editor of the book of essays, the year of publication, and the span of pages that the essay occupies. Thus:

Holderness, Graham "More to say on the Henriads" Shakespeare's History Plays Bryan Loughrey (editor) (1995) 5-49

Some stylists require that you put different bits of typographical furniture around the elements in the record--some want commas, some want periods, some want colons--but no-one's going to punish you in respect of such detail so long as you are consistent in your own styling. Spaces (as I've used) are quite acceptable so long as the record is unambiguous. The important thing is that you include the information that's wanted, don't include what isn't wanted, and that you correctly identify this as an essay by Holderness in a book of essays put together by Loughrey. (Don't make the mistake of entering the whole book in your list of works cited.)

Do the above and you need never again fight with Microsoft Word's execrable 'footnote/endnote' function and need never lose marks for poor referencing. If you have a lot of references to cope with (say, in your dissertation) use a 'personal bibliographical database' that manages your records and writes the list of works cited for you. The best one available is the free package Zotero (just Google it).

Rhetorical terms

anadiplosis (repeating the end of one sentence at the start of the next)

anaphora (repetition at the beginning of a sentence)

anastrophe (inversion of conventional order)

aposiopesis (breaking off)

asyndeton (omitting coordinators)

chiasmus (reversal of structure)

conduplicatio (non-consecutive word repetition)

ellipsis (omitting words more generally)

epanalepsis (repetition at both the beginning and the end of a sentence)

epimone (consecutive phrase repetition)

epistrophe (repetition at the end of a sentence or sentence-sequence)

epizeuxis (consecutive word repetition)

erotema (rhetorical questioning)

hypophora (asking a question and answering it)

isocolon (repetition of similar structure)

litotes (saying something by denying its opposite)

metanoia (self-correction)

polyptoton (repeating a root with a different inflectional ending)

polysyndeton (use of additional coordinators)

praeteritio (saying something by saying that you will not say it)

prolepsis (anticipating an objection and answering it).

symploce (repetition at both the beginning and the end of successive sentences)

(Source: Geoffrey Pullum's THES review of Farnsworth Classical English Rhetoric, 11 August 2011)

What is a PhD, exactly?

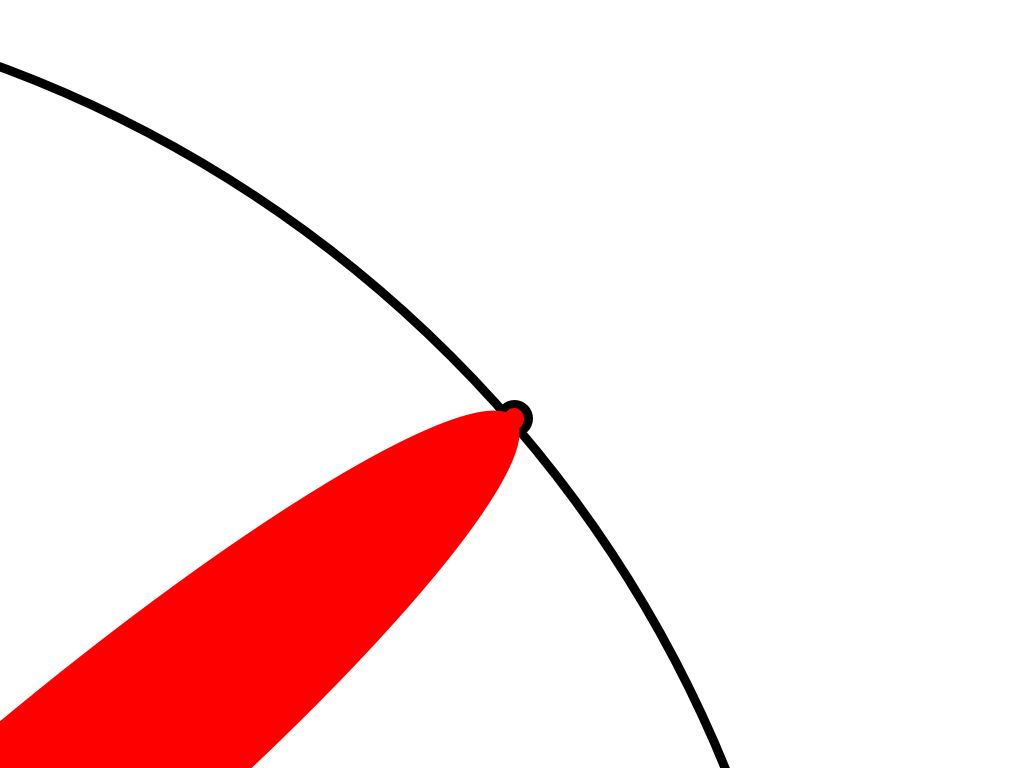

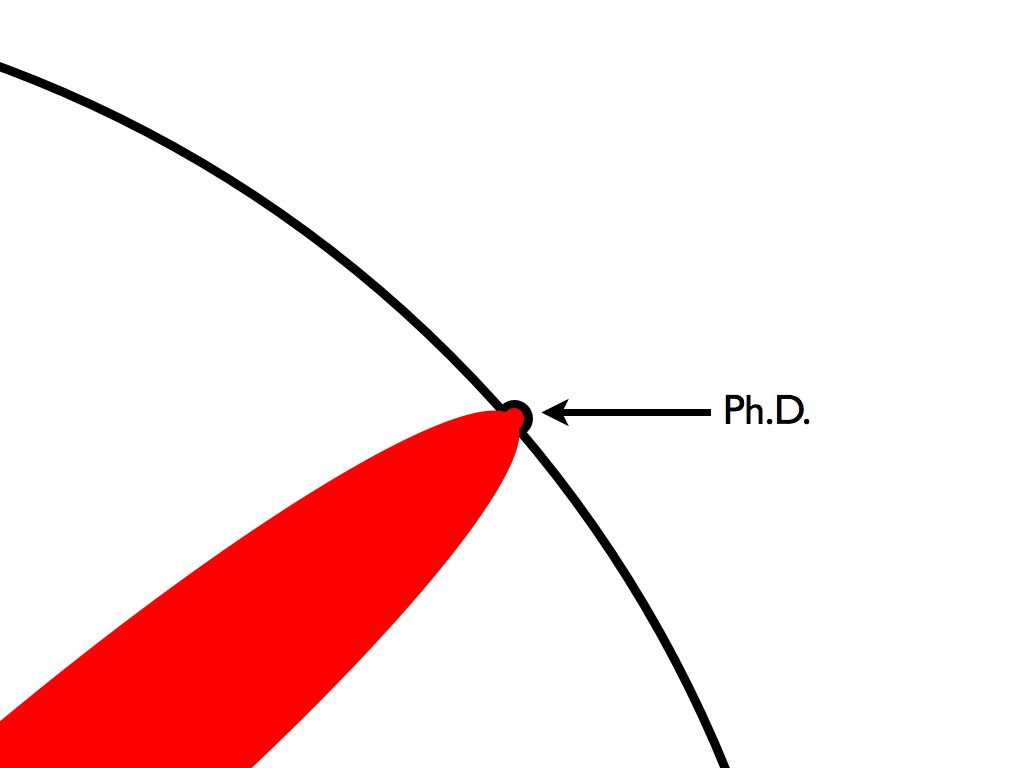

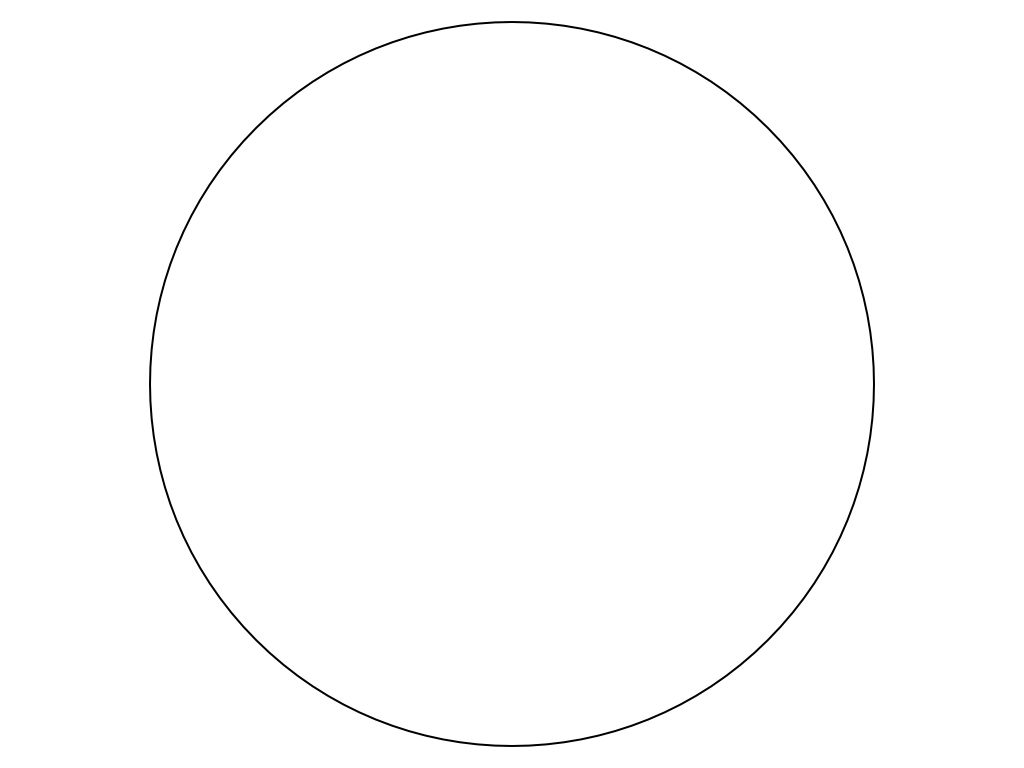

What follows is an adaptation of the visual explanation called "The Illustrated Guide to a PhD" produced by Matt Might of University of Utah, showing how a PhD relates to the world's knowledge. The images and ideas are all his: I've just altered the captions a little to suit British usage and tweaked an expression or two.

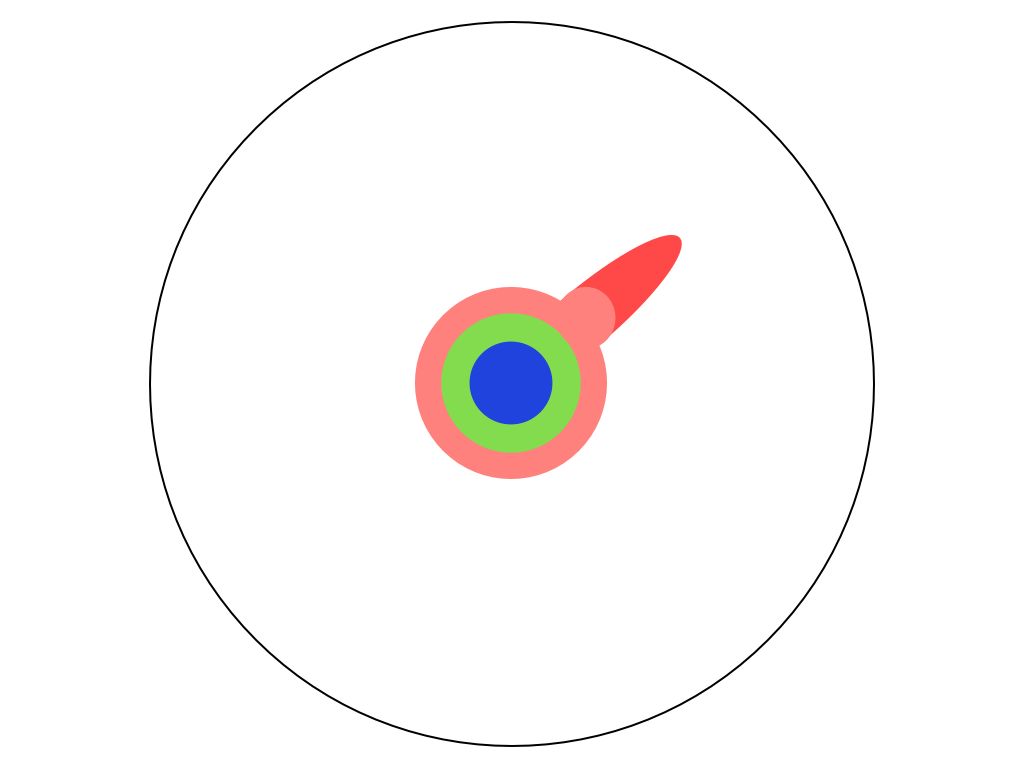

This circle represents all of human knowledge:

By the time you finish primary school, you know a little:

By the time you finish secondary school, you know a bit more:

With an undergraduate (BA) degree, you gain a speciality:

A Master's degree (MA) deepens that specialty:

Reading research papers takes you to the edge of human knowledge:

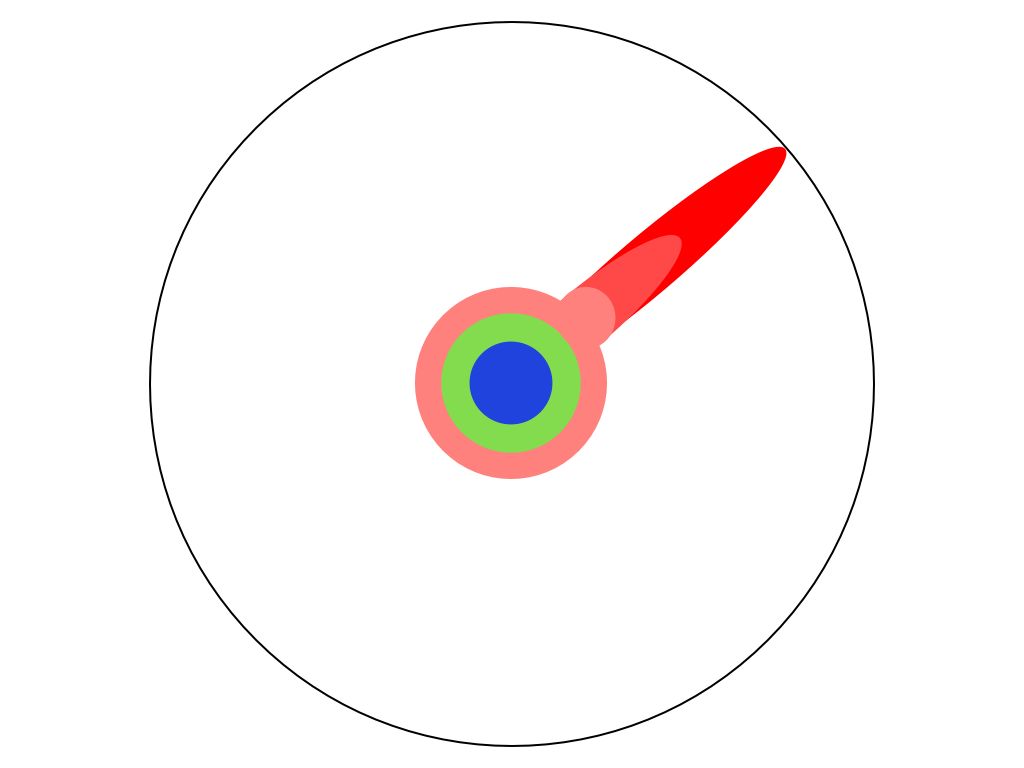

Once you're at the boundary, you focus:

You push at the boundary for a few years:

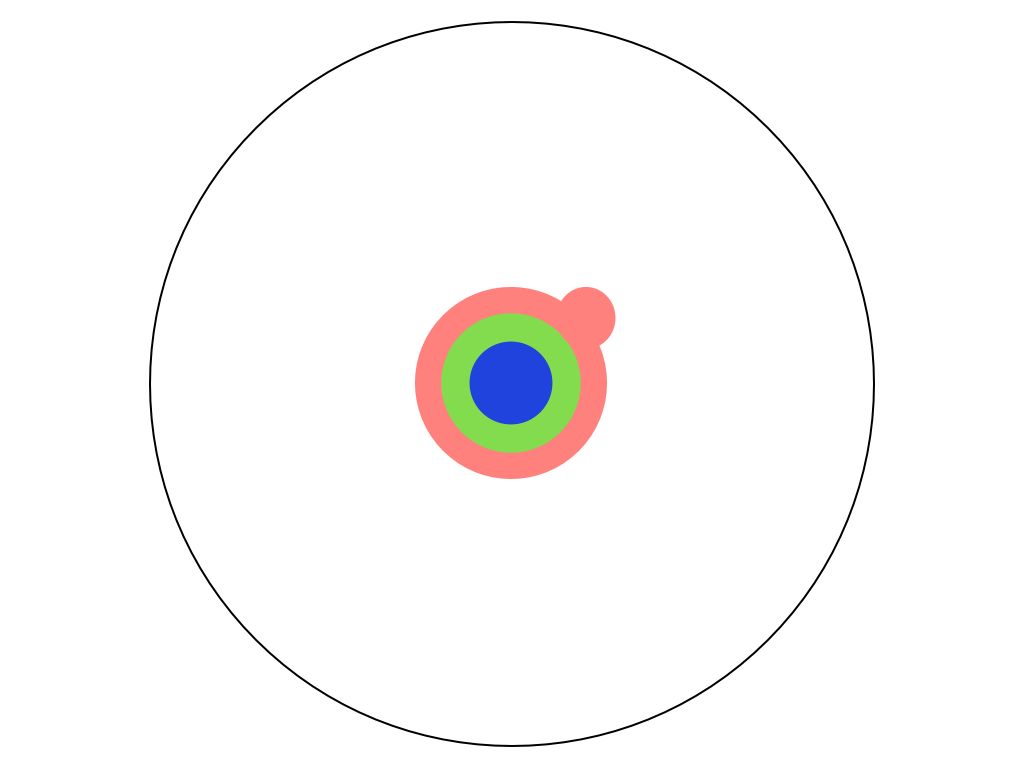

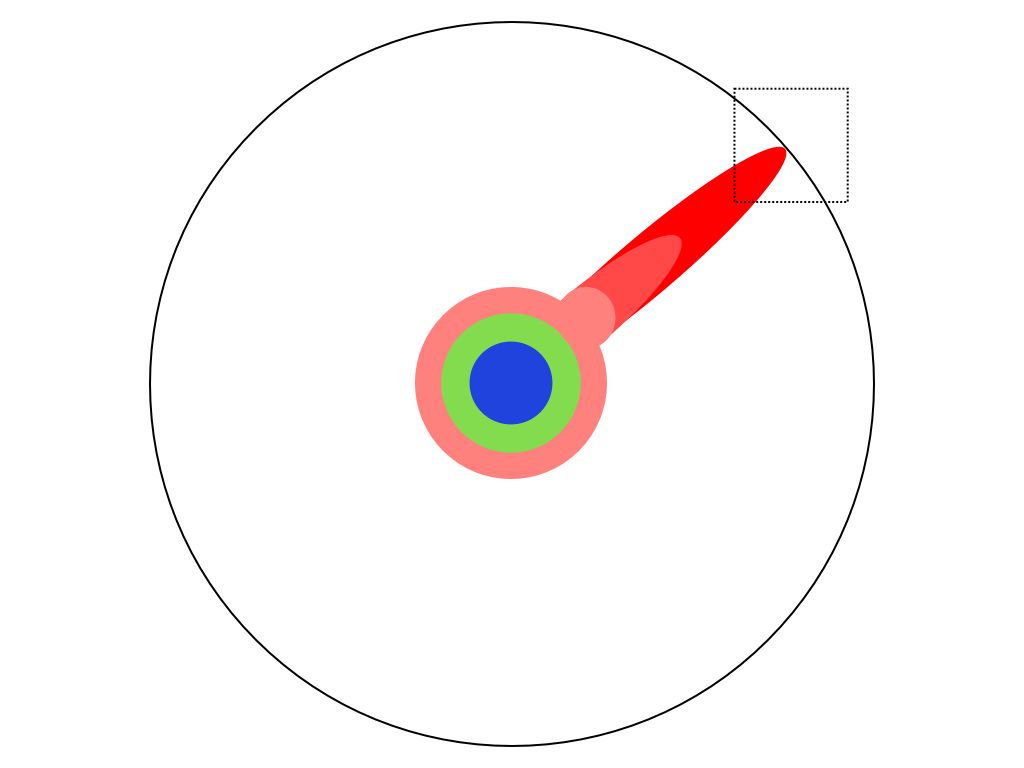

Until one day, the boundary gives way:

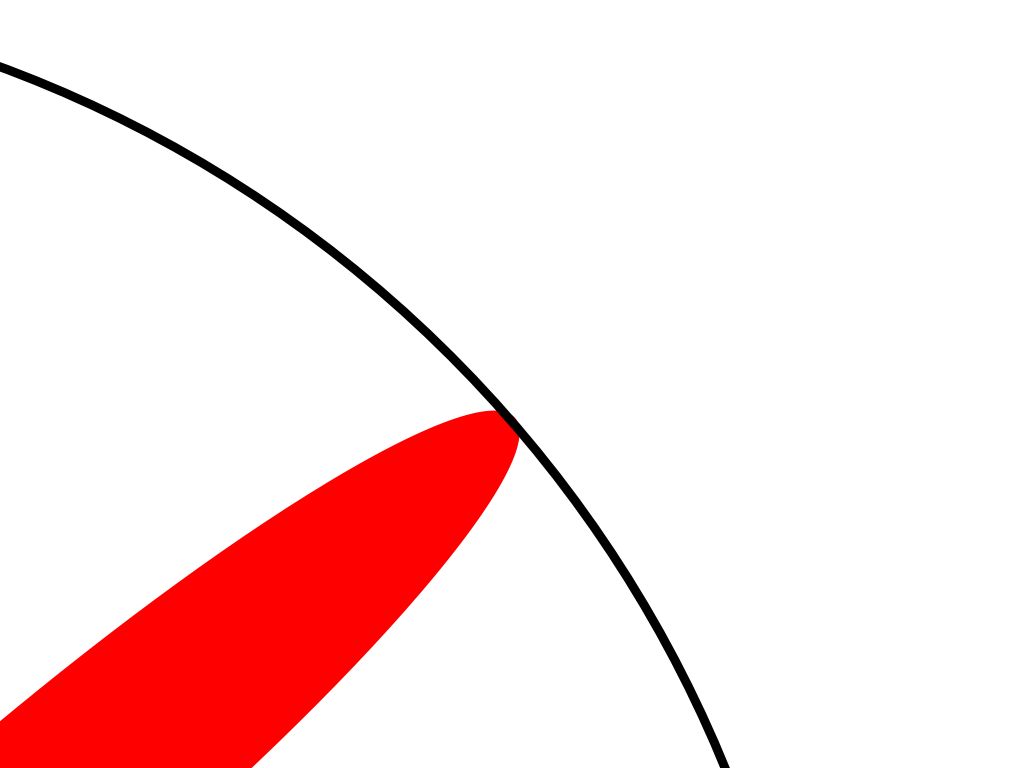

And, that dent you've made is called a Ph.D:

Of course, thousands of other people are making their own dents at the same time, so the circle of human knowledge is expanding in all directions at once:

If you continue to research, you continue to expand the circle. The next generation's starting point will be bigger than the last's. Remember learning the structure of the atom in school? That was cutting-edge research 100 years ago . . .

. . . so keep pushing.

How to write a PhD proposal

When applying for a PhD programme (or an MPhil as a route towards a PhD) you will doubtless be required to submit a research proposal as part of the application, and from the point of view of the academics in the department where you want to undertake the research this is the most important element of the application. Necessarily, research is an activity with unknown outcomes and it is in part directed by discoveries along the way, so one cannot state at the outset precisely what one hopes to discover. But one can give a sense of the project, and perhaps the most useful analogy would be to think of yourself as an explorer trying to persuade a patron to support an expedition you wish to undertake. You cannot state what you will find in the undiscovered region to which you want to travel, but you can state where you will be looking, what tools (maps, guides, and other resources) you will be taking, what means of transport you will adopt, how you will determine your route, and what things might be found when you reach wherever it is you will end up. Likewise there are analogous things that can be said about the journey of a research project, and it is the job of the research proposal to articulate these things. You should not feel bound to the proposal, rather it is an indication of the direction in which your research will go. The proposal helps the department assess your research potential

A research proposal is often developed by beginning with the following considerations:

What is the central question I wish to address?

What kinds of answers am I looking for?

What methods will help me find the answers?

What is the relationship between my central question and current work in the discipline/subject/area?

Am I sufficiently interested in this question to sustain my engagement with it over a prolonged period of study?

What kinds of benefits, personally or professionally, might derive from my research?

You should, if possible, discuss your ideas with your current Head of Department/tutor/supervisor, and/or with someone who has experience in the field in which you are interested.

The research proposal itself should give your name, the title of your research, and the degree for which it is intended, followed by:

description of your research topic in around 300 to 700 words, which foregrounds the basic question that forms the core of your enquiry, and includes a summary of the overall scope of your topic, as well as providing some information on the methods/approach/theory which you will be adopting.

a set of chapter headings each followed by a short outline of the chapter's likely content;

a bibliography of the reading which you consider to be relevant to your research , using an asterisk to mark those titles which you have already consulted;

a plan of work or a timetable for the proposed research showing the separate stages of your research, indicating how long these stages will last, and in what order they will be undertaken.

It should be possible to fit the whole research proposal onto two typed sheets of A4 paper. It should not be longer than three typed sheets.

Qualifications Students must, normally, have a good 2.1 degree from a British University or equivalent.

Time Scale and Stages of Application On receipt of your application form, your application will be considered by the Research Coordinator of the school/department to which you are applying. If your application and research proposal conform to the requirements of the department, the Research Coordinator will then approach a potential supervisor. You may be called for interview at this stage if this is appropriate. Finally, you will receive the school/department's formal decision, usually through the Postgraduate Office.

Printing Workshops for Doctoral Training Programme

Three videos to watch:

Bibliography 2 -- The Handpress

Bibliography 3 -- Using the Handpress